ব্যবহারকারী:Nokib Sarkar/রাজনৈতিক মতাদর্শ

মিল্টন রকিচ

[সম্পাদনা]হান্স যে আইসেনের কা সন্তুষ্ট না হতে পেরে মিল্টন রোকিচ ১৯৭৩ সালে স্বাধীনতা ও সমতার উপর ভিত্তি করে রাজনৈতিক মূল্যবোধের নিজস্ব দুটি অক্ষীয় মডেল তৈরি করেন এবং তাঁর The Nature of Human Values বইয়ে বর্ণনা করেন[১]।

মিল্টন রোকিচ দাবি করেছেন যে বাম এবং ডানের মধ্যে পার্থক্য নির্ধারণের ক্ষেত্রে বাম-দিকটি ডানদিকের চেয়ে অধিক সাম্যের গুরুত্বকে জোর দিয়েছিল। আইসেনের কট্টর-কোমল অক্ষের সমালোচনার সত্ত্বেও রোকিচ সাম্যবাদ ও নাৎসিবাদের মধ্যে মৌলিক সাদৃশ্য হিসেবে দাবি করেন যে এই দলগুলি সমাজতান্ত্রিক গণতন্ত্র , গণতান্ত্রিক সমাজতন্ত্র ও পুঁজিবাদীদের মতো স্বাধীনতাকে গুরুত্ব দেবে না এবং তিনি লিখেন যে "এখানে উপস্থাপিত দুটি মূল্যবোধের মডেল শুধুমাত্র আইযেনের অনুমান"।[১]

এই মডেলটি পরীক্ষা করতে মিল্টন রোকিচ এবং তার সহকর্মীরা নাৎসিবাদ (অ্যাডলফ হিটলার লিখিত), সাম্যবাদ (ভ্লাদিমির লেনিন লিখিত), পুঁজিবাদ (ব্যারি গোল্ডওয়াটার লিখিত) এবং সমাজতন্ত্র (বিভিন্ন সমাজতান্ত্রিক লেখক দ্বারা লিখিত)-এর বিষয়বস্তু বিশ্লেষণ করেন। বিশ্লেষণের অধীনে থাকা বিষয়বস্তুর সাথে পরীক্ষকের এবং গবেষকের বিশেষ রাজনৈতিক দৃষ্টিভঙ্গি উপর নির্ভরতার জন্য এই পদ্ধতিটি সমালোচিত হয়েছে।

Multiple raters made frequency counts of sentences containing synonyms for a number of values identified by Rokeach—including freedom and equality—and Rokeach analyzed these results by comparing the relative frequency rankings of all the values for each of the four texts:

- Socialists (socialism) — freedom ranked 1st, equality ranked 2nd

- Hitler (Nazism) – freedom ranked 16th, equality ranked 17th

- Goldwater (capitalism) — freedom ranked 1st, equality ranked 16th

- Lenin (communism) — freedom ranked 17th, equality ranked 1st

Later studies using samples of American ideologues[২] and American presidential inaugural addresses attempted to apply this model.[৩]

পরবর্তী গবেষণা

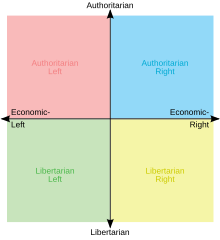

[সম্পাদনা]In further research,[৪] Hans J. Eysenck refined his methodology to include more questions on economic issues. Doing this, he revealed a split in the left–right axis between social policy and economic policy, with a previously undiscovered dimension of socialism-capitalism (S-factor).

While factorially distinct from Eysenck's previous R factor, the S-factor did positively correlate with the R-factor, indicating that a basic left–right or right–left tendency underlies both social values and economic values, although S tapped more into items discussing economic inequality and big business, while R relates more to the treatment of criminals and to sexual issues and military issues.

Most research and political theory since this time has replicated the factors shown above.[তথ্যসূত্র প্রয়োজন]

Another replication came from Ronald Inglehart's research into national opinions based on the World Values Survey, although Inglehart's research described the values of countries rather than individuals or groups of individuals within nations. Inglehart's two-factor solution took the form of Ferguson's original religionism and humanitarianism dimensions; Inglehart labelled them "secularism–traditionalism", which covered issues of tradition and religion, like patriotism, abortion, euthanasia and the importance of obeying the law and authority figures, and "survivalism – self expression", which measured issues like everyday conduct and dress, acceptance of diversity (including foreigners) and innovation and attitudes towards people with specific controversial lifestyles such as homosexuality and vegetarianism, as well as willingness to engage in political activism. See[৫] for Inglehart's national chart.

অন্যান্য দ্বি-অক্ষ মডেল

[সম্পাদনা]গ্রীনবার্গ এবং জোনাস: বাম ডান, মতাদর্শিক দৃঢ়তা

[সম্পাদনা]In a 2003 Psychological Bulletin paper,[৬] Jeff Greenberg and Eva Jonas posit a model comprising the standard left–right axis and an axis representing ideological rigidity. For Greenberg and Jonas, ideological rigidity has "much in common with the related concepts of dogmatism and authoritarianism" and is characterized by "believing in strong leaders and submission, preferring one’s own in-group, ethnocentrism and nationalism, aggression against dissidents, and control with the help of police and military". Greenberg and Jonas posit that high ideological rigidity can be motivated by "particularly strong needs to reduce fear and uncertainty" and is a primary shared characteristic of "people who subscribe to any extreme government or ideology, whether it is right-wing or left-wing".

Inglehart: traditionalist–secular and self expressionist–survivalist

[সম্পাদনা]

In its 4 January 2003 issue, The Economist discussed a chart,[৫] proposed by Ronald Inglehart and supported by the World Values Survey (associated with the University of Michigan), to plot cultural ideology onto two dimensions. On the y-axis it covered issues of tradition and religion, like patriotism, abortion, euthanasia and the importance of obeying the law and authority figures. At the bottom of the chart is the traditionalist position on issues like these (with loyalty to country and family and respect for life considered important), while at the top is the secular position. The x-axis deals with self-expression, issues like everyday conduct and dress, acceptance of diversity (including foreigners) and innovation, and attitudes towards people with specific controversial lifestyles such as vegetarianism, as well as willingness to engage in political activism. At the right of the chart is the open self-expressionist position, while at the left is its opposite position, which Inglehart calls survivalist. This chart not only has the power to map the values of individuals, but also to compare the values of people in different countries. Placed on this chart, European Union countries in continental Europe come out on the top right, Anglophone countries on the middle right, Latin American countries on the bottom right, African, Middle Eastern and South Asian countries on the bottom left and ex-Communist countries on the top left.

Pournelle: liberty–control, irrationalism–rationalism

[সম্পাদনা]This very distinct two-axis model was created by Jerry Pournelle in 1963 for his doctoral dissertation in political science. The Pournelle chart has liberty on one axis, with those on the left seeking freedom from control or protections for social deviance and those on the right emphasizing state authority or protections for norm enforcement (farthest right being state worship, farthest left being the idea of a state as the "ultimate evil"). The other axis is rationalism, defined here as the belief in planned social progress, with those higher up believing that there are problems with society that can be rationally solved and those lower down skeptical of such approaches.

Mitchell: Eight Ways to Run the Country

[সম্পাদনা]

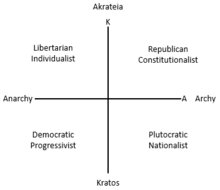

In 2006, Brian Patrick Mitchell identified four main political traditions in Anglo-American history based on their regard for kratos (defined as the use of force) and archē or "archy" (defined as the recognition of rank).[৭] Mitchell grounded the distinction of archy and kratos in the West's historical experience of church and state, crediting the collapse of the Christian consensus on church and state with the appearance of four main divergent traditions in Western political thought:

- Republican constitutionalism = pro archy, anti kratos

- Libertarian individualism = anti archy, anti kratos

- Democratic progressivism = anti archy, pro kratos

- Plutocratic nationalism = pro archy, pro kratos

Mitchell charts these traditions graphically using a vertical axis as a scale of kratos/akrateia and a horizontal axis as a scale of archy/anarchy. He places democratic progressivism in the lower left, plutocratic nationalism in the lower right, republican constitutionalism in the upper right, and libertarian individualism in the upper left. The political left is therefore distinguished by its rejection of archy, while the political right is distinguished by its acceptance of archy. For Mitchell, anarchy is not the absence of government but the rejection of rank. Thus there can be both anti-government anarchists (Mitchell’s "libertarian individualists") and pro-government anarchists (Mitchell's "democratic progressives", who favor the use of government force against social hierarchies such as patriarchy). Mitchell also distinguishes between left-wing anarchists and right-wing anarchists, whom Mitchell renames "akratists" for their opposition to the government’s use of force.

From the four main political traditions, Mitchell identifies eight distinct political perspectives diverging from a populist center. Four of these perspectives (Progressive, Individualist, Paleoconservative, and Neoconservative) fit squarely within the four traditions; four others (Paleolibertarian, Theoconservative, Communitarian, and Radical) fit between the traditions, being defined by their singular focus on rank or force. Anthony Gregory of the Independent Institute credits Mitchell with "the best explanation of the political spectrum", saying he "makes sense of all the major mysteries".[৮]

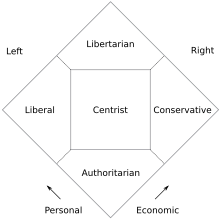

Nolan: economic freedom, personal freedom

[সম্পাদনা]

The Nolan Chart was created by libertarian David Nolan. This chart shows what he considers as "economic freedom" (issues like taxation, free trade and free enterprise) on the horizontal axis and what he considers as "personal freedom" (issues like drug legalization, abortion and the draft) on the vertical axis. This puts left-wingers in the left quadrant, libertarians in the top, right-wingers in the right and what Nolan originally named populists in the bottom.

Three-axis models

[সম্পাদনা]

One alternative spectrum offered by the conservative American Federalist Journal[৯] accounts for only the "degree of government control" without consideration for any other social or political variable and thus places "fascism" (totalitarianism) at one extreme and "anarchism" (no government at all) at the other extreme.

The Vosem Chart, or Vosem Cube, is based on the Nolan Chart and adds a third axis for corporate issues, depicted three dimensionally, with eight discrete categories representing eight different political ideologies. Vosem is the Russian word for "eight."[তথ্যসূত্র প্রয়োজন]

Other proposed dimensions

[সম্পাদনা]

In 1998, political author Virginia Postrel, in her book The Future and Its Enemies, offered another single-axis spectrum that measures views of the future, contrasting stasists, who allegedly fear the future and wish to control it, and dynamists, who want the future to unfold naturally and without attempts to plan and control. The distinction corresponds to the utopian versus dystopian spectrum used in some theoretical assessments of liberalism and the book's title is borrowed from the work of the anti-utopian classic-liberal theorist Karl Popper.

Other proposed axes include:

- Focus of political concern: communitarianism vs. individualism. These labels are preferred[১৮] to the loaded language of "totalitarianism" (anti-freedom) vs. "libertarianism" (pro-freedom), because one can have a political focus on the community without being totalitarian and undemocratic. Council communism is a political philosophy that would be counted as communitarian on this axis, but is not totalitarian or undemocratic.

- Responses to conflict: according to the political philosopher Charles Blattberg, those who would respond to conflict with conversation should be considered as on the left, with negotiation as in the centre, and with force as on the right. See his essay "Political Philosophies and Political Ideologies".[১৯]

- Role of the church: clericalism vs. anti-clericalism. This axis is less significant in the United States (where views of the role of religion tend to be subsumed into the general left–right axis) than in Europe (where clericalism versus anti-clericalism is much less correlated with the left–right spectrum).

- Urban vs. rural: this axis is significant today in the politics of Europe, Australia and Canada. The urban vs. rural axis was equally prominent in the United States' political past, but its importance is debatable at present. In the late 18th century and early 19th century in the United States, it would have been described as the conflict between Hamiltonian Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans.

- Foreign policy: interventionism (the nation should exert power abroad to implement its policy) vs. non-interventionism (the nation should keep to its own affairs). Similarly, multilateralism (coordination of policies with other countries) vs. isolationism and unilateralism

- Geopolitics: relations with individual states or groups of states may also be vital to party politics. During the Cold War, parties often had to choose a position on a scale between pro-American and pro-Soviet Union, although this could at times closely match a left–right spectrum. At other times in history relations with other powerful states has been important. In early Canadian history relations with Great Britain were a central theme, although this was not "foreign policy" but a debate over the proper place of Canada within the British Empire.

- International action: multilateralism (states should cooperate and compromise) versus unilateralism (states have a strong, even unconditional, right to make their own decisions).

- Political violence: pacifism (political views should not be imposed by violent force) vs. militancy (violence is a legitimate or necessary means of political expression). In North America, particularly in the United States, holders of these views are often referred to as "doves" and "hawks", respectively.

- Foreign trade: globalization (world economic markets should become integrated and interdependent) vs. autarky (the nation or polity should strive for economic independence). During the early history of the Commonwealth of Australia, this was the major political continuum. At that time it was called free trade vs. protectionism.

- Trade freedom vs. trade equity: free trade (businesses should be able trade across borders without regulations) vs. fair trade (international trade should be regulated on behalf of social justice).

- Diversity: multiculturalism (the nation should represent a diversity of cultural ideas) vs. assimilationism or nationalism (the nation should primarily represent, or forge, a majority culture).

- Participation: democracy (rule of the majority) vs. aristocracy (rule by the enlightened, elitism) vs. tyranny (total degradation of Aristocracy, ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle recognized tyranny as a state in which the tyrant is ruled by utter passion, and not reason like the philosopher, resulting in the tyrant pursuing his own desires rather than the common good.)

- Freedom: positive liberty (having rights which impose an obligation on others) vs. negative liberty (having rights which prohibit interference by others).

- Social power: totalitarianism vs. anarchism (control vs. no control) Analyzes the fundamental political interaction among people, and between individuals and their environment. Often posits the existence of a moderate system as existing between the two extremes.

- Change: radicals (who believe in rapid change) and progressives (who believe in measured, incremental change) vs. conservatives (who believe in preserving the status quo) vs. reactionaries (who believe in changing things to a previous state).

- Origin of state authority: popular sovereignty (the state as a creation of the people, with enumerated, delegated powers) vs. various forms of absolutism and organic state philosophy (the state as an original and essential authority) vs. the view held in anarcho-primitivism that "civilization originates in conquest abroad and repression at home".[২০]

- Levels of sovereignty: unionism vs. federalism vs. separatism; or centralism vs. regionalism. Especially important in societies where strong regional or ethnic identities are political issues.

- European integration (in Europe): Euroscepticism vs. European federalism; nation state vs. multinational state.

- Openness: closed (culturally conservative and protectionist) vs. open (socially liberal and globalist). Popularised as a concept by Tony Blair in 2007 and increasingly dominant in 21st century European and North American politics.[২১][২২]

রাজনৈতিক বর্ণালীভিত্তিক ভবিষ্যদ্বাণী

[সম্পাদনা]রাশিয়ান রাজনৈতিক বিজ্ঞানী স্টিফেন এস সুলক্ষন[২৩] দেখিয়েছেন যে রাজনৈতিক বর্ণালী পূর্বাভাসের সরঞ্জাম হিসাবে ব্যবহার করা যেতে পারে। সুলকশিন গাণিতিকভাবে প্রমাণ দিয়েছেন যে স্থিতিশীল উন্নয়ন (পরিসংখ্যানের সূচকসমূহের ইতিবাচক গতিবিধি) রাজনৈতিক বর্ণালীর প্রশস্ততার উপর নির্ভর করে: যদি এটি খুব সংকীর্ণ বা খুব বিস্তৃত হয় তবে অর্থনীতির স্থবিরতা বা রাজনৈতিক বিপর্যয় ঘটবে। সুলক্ষণ আরো দেখান যে, স্বল্প পরিসরে রাজনৈতিক বর্ণালী পরিসংখ্যানভিত্তিক সূচকসমূহের গতিবিধি নিয়ন্ত্রণ করে।

আরও দেখুন

[সম্পাদনা]- Cleavage (politics)

- Horseshoe theory

- রাজনীতিবিষয়ক নিবন্ধ সমূহের তালিকা

- বাম-ডানপন্থী রাজনীতি

- NationStates

- Psephology

References

[সম্পাদনা]- ↑ ক খ Rokeach, Milton (১৯৭৩)। The nature of human values। Free Press।

- ↑ Rous, G.L.; Lee, D.E. (Winter ১৯৭৮)। "Freedom and Equality: Two values of political orientation"। Journal of Communication। 28: 45–51। ডিওআই:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01561.x।

- ↑ Mahoney, J.; Coogle, C.L.; Banks, P.D. (১৯৮৪)। "Values in presidential inaugural addresses: A test of Rokeach's two-factor theory of political ideology"। Psychological Reports। 55 (3): 683–6। ডিওআই:10.2466/pr0.1984.55.3.683। ১৪ মে ২০১৩ তারিখে মূল থেকে আর্কাইভ করা।

- ↑ Eysenck, Hans (১৯৭৬)। "The structure of social attitudes"। Psychological Reports। 39 (2): 463–6। ডিওআই:10.2466/pr0.1976.39.2.463। ১৪ মে ২০১৩ তারিখে মূল থেকে আর্কাইভ করা।

- ↑ ক খ Inglehart, Ronald; Welzel, Christian। "The WVS Cultural Map of the World"। World Values Survey। Archived from the original on ৩১ অক্টোবর ২০১১। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ১৮ ডিসেম্বর ২০১৩।

- ↑ Greenberg, J.; Jonas, E. (২০০৩)। "Psychological Motives and Political Orientation—The Left, the Right, and the Rigid: Comment on Jost et al. (2003)" (পিডিএফ)। Psychological Bulletin। 129 (3): 376–382। ডিওআই:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.376। সাইট সিয়ারX 10.1.1.396.6599

।

।

- ↑ Mitchell, Brian Patrick (২০০৭)। Eight ways to run the country: a new and revealing look at left and right। Greenwood Publishing। আইএসবিএন 978-0-275-99358-0।

- ↑ Gregory, Anthony, "What About the 'Real' Left?" ওয়েব্যাক মেশিনে আর্কাইভকৃত ১৮ জুন ২০১৫ তারিখে, Lewrockwell.com, 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "American Federalist Journal – News and opinion about politics, culture and current events"। ১৫ অক্টোবর ২০০৫ তারিখে মূল থেকে আর্কাইভ করা। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ৫ মে ২০১৬।

- ↑ Heywood, Andrew (২০১৭)। Political Ideologies: An Introduction (6th সংস্করণ)। Basingstoke: Macmillan International Higher Education। পৃষ্ঠা 14–17। আইএসবিএন 9781137606044। ওসিএলসি 988218349।

- ↑ Love, Nancy Sue (২০০৬)। Understanding Dogmas and Dreams (Second সংস্করণ)। Washington, District of Columbia: CQ Press। পৃষ্ঠা 16। আইএসবিএন 9781483371115। ওসিএলসি 893684473।

- ↑ উদ্ধৃতি ত্রুটি:

<ref>ট্যাগ বৈধ নয়;:5নামের সূত্রটির জন্য কোন লেখা প্রদান করা হয়নি - ↑ Sznajd-Weron, Katarzyna; Sznajd, Józef (জুন ২০০৫)। "Who is left, who is right?"। Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications (ইংরেজি ভাষায়)। 351 (2–4): 593–604। ডিওআই:10.1016/j.physa.2004.12.038।

- ↑ Forman, F. N.; Baldwin, N. D. J. (১৯৯৯)। Mastering British Politics (ইংরেজি ভাষায়)। London: Macmillan Education UK। পৃষ্ঠা 8 f। আইএসবিএন 9780333765487। ডিওআই:10.1007/978-1-349-15045-8।

- ↑ Fenna, Alan; Robbins, Jane; Summers, John (২০১৩)। Government Politics in Australia। Robbins, Jane., Summers, John. (10th সংস্করণ)। Melbourne: Pearson Higher Education AU। পৃষ্ঠা 126 f। আইএসবিএন 9781486001385। ওসিএলসি 1021804010।

- ↑ Jones, Bill; Kavanagh, Dennis (২০০৩)। British Politics Today। Kavanagh, Dennis. (7th সংস্করণ)। Manchester: Manchester University Press। পৃষ্ঠা 259। আইএসবিএন 9780719065095। ওসিএলসি 52876930।

- ↑ Körösényi, András (১৯৯৯)। Government and Politics in Hungary। Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press। পৃষ্ঠা 54। আইএসবিএন 9639116769। ওসিএলসি 51478878।

- ↑ Horrell, David (২০০৫)। "Paul Among Liberals and Communitarians"। Pacifica। 18 (1): 33–52। hdl:10036/35872। ডিওআই:10.1177/1030570X0501800103।

- ↑ Blattberg, Charles (২০০৯)। "Political Philosophies and Political Ideologies"। Patriotic Elaborations: Essays in Practical Philosophy। McGill-Queen's University Press। এসএসআরএন 1755117

।

।

- ↑ Diamond, Stanley, In Search Of The Primitive: A Critique Of Civilization, (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1981), p. 1.

- ↑ "The new political divide"। The Economist। ৩০ জুলাই ২০১৬। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৪ এপ্রিল ২০১৭।

- ↑ Pethokoukis, James (১ জুলাই ২০১৬)। "The Closed Party vs. the Open Party"। American Enterprise Institute। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৪ এপ্রিল ২০১৭।

- ↑ Sulakshin, S. (২০১০)। "A Quantitative Political Spectrum and Forecasting of Social Evolution"। International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences। 5 (4): 55–66। ডিওআই:10.18848/1833-1882/CGP/v05i04/51654।