ব্যবহারকারী:Muhammad/বহির্গ্রহ

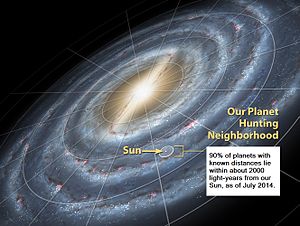

An extrasolar planet, or exoplanet, is a planet outside the Solar System. Around a thousand such planets have been discovered (৭৬০ planets in ৬০৯ planetary systems including ১০০ multiple planetary systems as of ২০১২ সালের ৭ই মার্চ).[৫] The Kepler mission space telescope has detected thousands more candidate planets, including 262 that may be habitable planets.[৬][৭] In the Milky Way galaxy, it is expected that there are many billions of planets (at least one planet, on average, orbiting around each star, resulting in 100–400 billion exoplanets),[১][২][৩][৮] with many more free-floating planetary-mass bodies orbiting within the galaxy.[৯] In 2013, it was estimated that there are at least 17 billion Earth-sized planets in the Milky Way.[১০] The nearest exoplanet, if confirmed, would be Alpha Centauri Bb but there is some doubt about its existence. Almost all of the planets detected so far are within our home galaxy the Milky Way; however, there have been a small number of possible detections of extragalactic planets.

For centuries, many philosophers and scientists supposed that extrasolar planets existed, but there was no way of knowing how common they were or how similar they might be to the planets of the Solar System. Various detection claims, starting in the nineteenth century, were all eventually rejected by astronomers. The first confirmed detection came in 1992, with the discovery of several terrestrial-mass planets orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12.[১১] The first confirmed detection of an exoplanet orbiting a main-sequence star was made in 1995, when a giant planet was found in a four-day orbit around the nearby star 51 Pegasi. Due to ongoing refinement in observational techniques, the rate of detections has increased rapidly since then.[৫] Some exoplanets have been directly imaged by telescopes, but the vast majority have been detected through indirect methods such as radial velocity measurements.[৫] Besides exoplanets, "exocomets", comets beyond our solar system, have also been detected and may be common in the Milky Way galaxy.[১০]

Most known exoplanets are giant planets believed to resemble Jupiter or Neptune, but this reflects a sampling bias, as massive and larger planets are more easily observed.[১২] Some relatively lightweight exoplanets, only a few times more massive than Earth (now known by the term Super-Earth), are known as well; statistical studies now indicate that they actually outnumber giant planets[১৩] while recent discoveries have included Earth-sized and smaller planets and a handful that appear to exhibit other Earth-like properties.[১৪][১৫][১৬] There also exist planetary-mass objects that orbit brown dwarfs and other bodies that "float free" in space not bound to any star; however, the term "planet" is not always applied to these objects.

The discovery of extrasolar planets, particularly those that orbit in the habitable zone where it is possible for liquid water to exist on the surface (and therefore also life), has intensified interest in the search for extraterrestrial life.[১৭] Thus, the search for extrasolar planets also includes the study of planetary habitability, which considers a wide range of factors in determining an extrasolar planet's suitability for hosting life.

The most Earth-like planets in a habitable zone to have been discovered, as of April 2013, are Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f which have 1.61 and 1.41 Earth radii respectively.[১৮]

আবিষ্কারের ইতিহাস[সম্পাদনা]

প্রাচীন প্রজ্ঞা[সম্পাদনা]

| “ | এই মহাবিশ্বকে আমরা অসীম বলছি... এতে আমাদের আপন বিশ্বের মতোই অসংখ্য বিশ্ব রয়েছে। | ” |

| — জোর্দানো ব্রুনো (১৫৮৪)[১৯] | ||

ষোড়শ শতকে ইতালীয় দার্শনিক জোর্দানো ব্রুনো প্রস্তাব করেছিলেন যে, রাতের আকাশে দৃশ্যমান তারাগুলো আমাদের সূর্যের সদৃশ এবং তাদের চারদিকেও গ্রহ রয়েছে। উল্লেখ্য, ব্রুনো ছিলেন নিকোলাউস কোপের্নিকুস-এর সৌরকেন্দ্রিক মতবাদের প্রথম দিককার সমর্থকদের মধ্যে অন্যতম। ১৬০০ সালে ব্রুনোকে রোমান ক্যাথলিক চার্চের নির্দেশে পুড়িয়ে মারা হয়; তার জ্যোতির্বিজ্ঞান বিষয়ক চিন্তাভাবনাগুলো এ মৃত্যুদণ্ডের প্রধান কারণ ছিল না।[২০]

অষ্টাদশ শতকে আইজ্যাক নিউটন তার বিখ্যাত ফিলোসফিয়া নাতুরালিস প্রিংকিপিয়া মাথেমাটিকা গ্রন্থের শেষ অধ্যায় General Scholium-এ বহির্গ্রহের সম্ভাব্যতা বিষয়ে একই ধরণের মতামত ব্যক্ত করেছিলেন। সূর্যের গ্রহগুলোর সাথে তুলনা দিয়ে তিনি লিখেছিলেন, "স্থির তারাগুলোও যদি এমন তারকা জগতের মধ্যমণি হয়ে থাকে, তাহলে সে জগৎগুলোও একই ধরণের নকশা অনুযায়ী নির্মীত, এবং সেই 'একক সত্ত্বার'-ই বশবর্তী"।[২১]

ভুল প্রমাণিত দাবীসমূহ[সম্পাদনা]

ঊনবিংশ শতক থেকেই বিভিন্ন বহির্গ্রহ আবিষ্কারের দাবী উত্থাপিত হয়ে আসছে। একেবারে প্রথম দাবীগুলোর মধ্যে ছিল 70 Ophiuchi নামক যুগল তারার চারদিকে আবর্তনরত গ্রহ। ১৮৫৫ সালে ব্রিটিশ ইস্ট ইন্ডিয়া কোম্পানির কর্মকর্তা ক্যাপ্টেন ডব্লিউ এস জ্যাকব ভারতের মাদ্রাজ মানমন্দির থেকে তারাটি পর্যবেক্ষণের পর জানান যে, এর কক্ষপথে যে অস্বাভাবিকতা পরিলক্ষিত হয় তার কারণ হতে পারে কোনো গ্রহীয় বস্তু।[২২] ১৮৯০-এর দশকে ইউনিভার্সিটি অফ শিকাগো এবং ইউনাইটডে স্টেটস নেভাল অবজার্ভেটরি-তে কর্মরত টমাস জে জে সি একই সিদ্ধান্তে আসেন: কক্ষপথের অস্বাভাবিকতা 70 Ophiuchi তারা যুগলটির চারদিকে একটি অদৃশ্য বস্তুর উপস্থিতির সাক্ষ্য দেয়। এমনকি তিনি এই বস্তুটির আবর্তনকালও হিসাব করেন— তার মতে গ্রহটি তারা দু'টির যেকোন একটির চারদিকে প্রতি ৩৬ বছরে (পার্থিব) একবার আবর্তন করে।[২৩] কিন্তু ফরেস্ট রেই মোল্টন এ ধরণের কক্ষপথবিশিষ্ট তিনটি জ্যোতিষ্কের জগৎকে অস্থিতিশীল প্রমাণ করে একটি গবেষণাপত্র প্রকাশ করেন।[২৪] ১৯৫০ ও ১৯৬০-এর দশকে যুক্তরাষ্ট্রের সোয়ার্থমোর কলেজের পেটার ভান ডে কাম্প ধারাবাহিকভাবে বেশ কয়েকবার দাবী করেন যে, বার্নার্ডের তারার চারদিকে গ্রহ আছে।[২৫] এই প্রাথমিক দাবীগুলোকে বর্তমানে জ্যোতির্বিজ্ঞানীরা ত্রুটিপূর্ণ মনে করেন।[২৬]

১৯৯১ সালে অ্যান্ড্রু লিন, এম বেইল্স এবং এস এল শেমার পালসার কালনিরূপণ পদ্ধতি ব্যবহার করে পিএসআর ১৮২৯-১০ নামক পালসারটির চারদিকে আবর্তনরত একটি পালসার গ্রহ আবিষ্কারের দাবী করেন।[২৭] সাময়িকভাবে এ নিয়ে অনেক আলোচনা হলেও পরবর্তীতে লিন দাবীটি উঠিয়ে নেন।[২৮]

সুপ্রমাণিত আবিষ্কারসমূহ[সম্পাদনা]

বহির্গ্রহ আবিষ্কারের যে দাবীটি প্রথম নির্ভুল প্রমাণিত হয়, তা প্রথম উত্থাপন করেছিলেন কানাডার ভিক্টোরিয়া ও ব্রিটিশ কলাম্বিয়া বিশ্ববিদ্যালয়ের জ্যোতির্বিজ্ঞানী ব্রুস ক্যাম্পবেল, জি এ এইচ ওয়াকার, এবং স্টিফেনসন ইয়াং, ১৯৮৮ সালে।[২৯] তারা গামা সেফাই তারার অরীয় বেগ পরিমাপের মাধ্যমে বুঝতে পারেন যে, এর আশেপাশে কোনো গ্রহীয় বস্তু আছে, কিন্তু একে একেবারে গ্রহ দাবী করা থেকে বিরত থাকেন। এত সূক্ষ্ণ পর্যবেক্ষণের জন্য সমসাময়িক দুরবিনগুলো উপযুক্ত কি-না তা নিয়ে দ্বিধা থাকায় জ্যোতির্বিজ্ঞানীরা অনেকদিন পর্যন্ত এটি এবং এর মতো অন্যান্য আবিষ্কারগুলো নিয়ে সন্দিহান থাকেন। অনেকে ভাবতে থাকেন যে, এগুলো হয়ত ভবিষ্যতে বাদামী বামন হিসেবে প্রমাণিত হবে। গামা সেফাইয়ের চারদিকে গ্রহ থাকার সম্ভাবনা ১৯৯০ সালের আরেকটি পর্যবেক্ষণে প্রকট হয়ে উঠে,[৩০] কিন্তু ১৯৯২ সালে অনুবর্তী পর্যবেক্ষণ এ নিয়ে আবার সন্দেহের ধূম্রজাল সৃষ্টি করে।[৩১] অবশেষে ২০০৩ সালে উন্নততর পর্যবেক্ষণ কৌশল ব্যবহার করে গ্রহটির উপস্থিতি নিশ্চিত করা হয়।[৩২]

১৯৯২ সালের ২১শে এপ্রিল[৩৩] বেতার জ্যোতির্বিজ্ঞানী আলেকসান্দার ভোলস্টান এবং ডেইল ফ্রেইল PSR 1257+12 নামক পালসারের চারদিকে দুইটি গ্রহ আবিষ্কারের ঘোষণা দেন।[১১] এই আবিষ্কার নির্ভুল প্রমাণিত হয়েছে, এবং একেই সুনিশ্চিতভাবে আবিষ্কৃত প্রথম বহির্গ্রহ বিবেচনা করা হয়। পালসার যেহেতু অতিনবতারা বিস্ফোরণের পর তৈরি হয় সেহেতু বিস্ফোরণের পরও কিভাবে গ্রহের মতো একটি বস্তু টিকে থাকতে পেরেছে তা ব্যাখ্যা করার জন্য অনেকে বলেন, হয়ত অতিনবতারার অবশিষ্টাংশ থেকে গ্রহের উদ্ভবের দ্বিতীয় আরেকটি প্রক্রিয়া শুরু হয়েছিল, বা হয়ত লোহিত দানব তারার কিছু শিলাময় অংশ কোনো না কোনোভাবে বিস্ফোরণের ধ্বংসযজ্ঞ থেকে বেঁচে পরবর্তীতে গ্রহের রূপ নিয়েছে এবং ধীরে ধীরে পালসারটির চারদিকে একটি কক্ষপথে স্থির হয়েছে।

১৯৯৫ সালের ৬ই অক্টোবর জেনেভা বিশ্ববিদ্যালয়ের মিশেল মায়োর এবং দিদিয়ে কেলোজ প্রথম একটি মূলধারার তারার চারদিকে আবর্তনরত গ্রহ আবিষ্কারের ঘোষণা দেন; তারাটি ছিল জি-ধরনের ৫১ পেগাসি, আর গ্রহটি ৫১ পেগাসি বি।[৩৪] Observatoire de Haute-Provence এ হওয়া এই আবিষ্কার বহির্গ্রহ গবেষণার আধুনিক যুগের সূত্রপাত ঘটিয়েছে। এর পর সূক্ষ্ণ রেজল্যুশনের বর্ণালীবীক্ষণ যন্ত্র ব্যবহারের মাধ্যমে দ্রুত আবিষ্কৃত হতে থাকে আরও অনেক বহির্গ্রহ। এসব যন্ত্রে গ্রহের কারণে তারার সম্মুখ-পশ্চাৎ তথা অরীয় গতি ধরা পড়ে, যার ফলে গ্রহটি না দেখেও তার অস্তিত্ব সম্পর্কে নিশ্চিত হওয়া যায়। পরবর্তীতে অতিক্রমণ পদ্ধতিতে আরও অনেক গ্রহ আবিষ্কৃত হয়; এক্ষেত্রে মাতৃতারার সামনে দিয়ে গ্রহটি যাওয়ার সময় তারার উজ্জ্বলতার হ্রাস পরিমাপ করা হয়।

প্রথম দিকে আবিষ্কৃত অধিকাংশ গ্রহের আকার ছিল বৃহস্পতির সমান বা আরও বেশি, কিন্তু মাতৃতারা থেকে তাদের দূরত্ব ছিল খুবই কম; এ কারণে এদেরকে উষ্ণ বৃহস্পতি বলা হয়। জ্যোতির্বিজ্ঞানীরা এতে খুব বিস্মিত হয়েছিলেন, কারণ তখনকার প্রতিষ্ঠিত তত্ত্ব অনুসারে দানবীয় গ্রহ কেবল তারা থেকে অনেক দূরে গঠিত হতে পারে। পরবর্তীতে সকল ধরণের ভর ও দূরত্বের গ্রহই আবিষ্কৃত হতে থাকে, এবং কালক্রমে দেখা যায় যে, উষ্ণ বৃহস্পতির মতো গ্রহরাই সংখ্যালঘু। ১৯৯৯ সালে আপসিলন অ্যান্ড্রোমিডাই তারার চারদিকে একাধিক গ্রহ আবিষ্কৃত হয়; এটিই প্রথম মূলধারার তারা যার চারদিকে একাধিক গ্রহ পাওয়া গেছে।[৩৫] পরবর্তীতে বহুগ্রহ বিশিষ্ট আরও অনেক তারা জগৎ আবিষ্কৃত হয়।

এক্সট্রাসোলার প্ল্যানেটস এনসাইক্লোপিডিয়া-র তথ্য অনুসারে ২০১২ সালের ৭ই মার্চ তারিখ পর্যন্ত মোট ৭৬০টি বহির্গ্রহ নিশ্চিতভাবে আবিষ্কৃত হয়েছে। এর মধ্যে এমন কয়েকটি গ্রহও আছে ১৯৮০-র দশকেই যাদের অস্তিত্বের ভবিষ্যদ্বাণী করা হয়েছিল।[৫] এই গ্রহগুলোর মধ্যে ৬০৯টি গ্রহজগৎ, এবং ১০০টি একাধিক গ্রহবিশিষ্ট জগৎ। কেপলার-১৬ আবিষ্কৃত প্রথম গ্রহ যা একটি যুগল তারা জগৎকে আবর্তন করে।[৩৬]

Candidate discoveries[সম্পাদনা]

As of February 2012, NASA's Kepler mission had identified 2,321 planetary candidates associated with 1,790 host stars, based on the first sixteen months of data from the space-based telescope.[৩৭]

17 October 2012 brought news of an unverified planet, Alpha Centauri Bb, orbiting a star in the star system closest to Earth, Alpha Centauri. It is an Earth-size planet, but not in the habitable zone within which liquid water can exist.[৩৮]

Detection methods[সম্পাদনা]

Planets are extremely faint compared to their parent stars. At visible wavelengths, they usually have less than a millionth of their parent star's brightness. It is difficult to detect such a faint light source, and furthermore the parent star causes a glare that tends to wash it out. It is necessary to block the light from the parent star in order to reduce the glare, while leaving the light from the planet detectable; doing so is a major technical challenge.[৩৯]

All exoplanets that have been directly imaged are both large (more massive than Jupiter) and widely separated from their parent star. Most of them are also very hot, so that they emit intense infrared radiation; the images have then been made at infrared where the planet is brighter than it is at visible wavelengths.

Though direct imaging may become more important in the future, the vast majority of known extrasolar planets have only been detected through indirect methods. The following are the indirect methods that have proven useful:

- As a planet orbits a star, the star also moves in its own small orbit around the system's center of mass. Variations in the star's radial velocity — that is, the speed with which it moves towards or away from Earth — can be detected from displacements in the star's spectral lines due to the Doppler effect. Extremely small radial-velocity variations can be observed, of 1 m/s or even somewhat less.[৪০] This has been by far the most productive method of discovering exoplanets. It has the advantage of being applicable to stars with a wide range of characteristics. One of its disadvantages is that it cannot determine a planet's true mass, but can only set a lower limit on that mass. However, if the radial velocity of the planet itself can be distinguished from the radial velocity of the star then the true mass can be determined.[৪১]

- If a planet crosses (or transits) in front of its parent star's disk, then the observed brightness of the star drops by a small amount. The amount by which the star dims depends on its size and on the size of the planet, among other factors. This has been the second most productive method of detection, though it suffers from a substantial rate of false positives and confirmation from another method is usually considered necessary. The transit method reveals the radius of a planet, and it has the benefit that it sometimes allows a planet's atmosphere to be investigated through spectroscopy.

- Transit timing variation (TTV)

- When multiple planets are present, each one slightly perturbs the others' orbits. Small variations in the times of transit for one planet can thus indicate the presence of another planet, which itself may or may not transit. For example, variations in the transits of the planet Kepler-19b suggest the existence of a second planet in the system, the non-transiting Kepler-19c.[৪২][৪৩] If multiple transiting planets exist in one system, then this method can be used to confirm their existence.[৪৪] In another form of the method, timing the eclipses in an eclipsing binary star can reveal an outer planet that orbits both stars; as of August 2013, a few planets have been found in that way with numerous planets confirmed with this method.

- Transit duration variation (TDV)

- When a planet orbits multiple stars or if the planet has moons, its transit time can significantly vary per transit. While no new planets or moons have been discovered with this method, it is used to successfully confirm many transiting circumbinary planets.[৪৫]

- Microlensing occurs when the gravitational field of a star acts like a lens, magnifying the light of a distant background star. Planets orbiting the lensing star can cause detectable anomalies in the magnification as it varies over time. This method has resulted in only 13 detections as of June 2011, but it has the advantage of being especially sensitive to planets at large separations from their parent stars.

- Astrometry consists of precisely measuring a star's position in the sky and observing the changes in that position over time. The motion of a star due to the gravitational influence of a planet may be observable. Because the motion is so small, however, this method has not yet been very productive. It has produced only a few disputed detections, though it has been successfully used to investigate the properties of planets found in other ways.

- A pulsar (the small, ultradense remnant of a star that has exploded as a supernova) emits radio waves extremely regularly as it rotates. If planets orbit the pulsar, they will cause slight anomalies in the timing of its observed radio pulses. The first confirmed discovery of an extrasolar planet was made using this method. But as of 2011, it has not been very productive; five planets have been detected in this way, around three different pulsars.

- Variable star timing (pulsation frequency)

- Like pulsars, there are some other types of stars which exhibit periodic activity. Deviations from the periodicity can sometimes be caused by a planet orbiting it. As of 2013, a few planets have been discovered with this method.[৪৬]

- When a planet orbits very close to the star, it catches a considerable amount of starlight. As the planet orbits around the star, the amount of light changes due to planets having phases from Earth's viewpoint or planet glowing more from one side than the other due to temperature differences.[৪৭]

- Relativistic beaming measures the observed flux from the star due to its motion. The brightness of the star changes as it moves closer or further away from its host star.[৪৮]

- Massive planets close to their host stars can slightly deform the shape of the star. This causes the brightness of the star to slightly deviate depending how it is rotated relative to Earth.[৪৯]

- With polarimetry method, a polarized light reflected off the planet is separated from unpolarized light emitted from the star. No new planets have been discovered with this method although a few already discovered planets have been detected with this method.[৫০][৫১]

- Disks of space dust surround many stars, believed to originate from collisions among asteroids and comets. The dust can be detected because it absorbs starlight and re-emits it as infrared radiation. Features in the disks may suggest the presence of planets, though this is not considered a definitive detection method.

Most confirmed extrasolar planets have been found using ground-based telescopes. However, many of the methods can work more effectively with space-based telescopes that avoid atmospheric haze and turbulence. COROT (launched December 2006) and Kepler (launched March 2009) are the two currently active space missions dedicated to searching for extrasolar planets. Hubble Space Telescope and MOST have also found or confirmed a few planets. The Gaia mission, to be launched in November 2013,[৫২] will use astrometry to determine the true masses of 1000 nearby exoplanets.[৫৩][৫৪]

Definition[সম্পাদনা]

The official definition of "planet" used by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) only covers the Solar System and thus does not apply to exoplanets.[৫৫][৫৬] As of April 2011, the only definitional statement issued by the IAU that pertains to exoplanets is a working definition issued in 2001 and modified in 2003.[৫৭] That definition contains the following criteria:

- Objects with true masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium (currently calculated to be 13 Jupiter masses for objects of solar metallicity) that orbit stars or stellar remnants are "planets" (no matter how they formed). The minimum mass/size required for an extrasolar object to be considered a planet should be the same as that used in our solar system.

- Substellar objects with true masses above the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are "brown dwarfs", no matter how they formed or where they are located.

- Free-floating objects in young star clusters with masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are not "planets", but are "sub-brown dwarfs" (or whatever name is most appropriate).

This article follows the above working definition. Therefore it only discusses planets that orbit stars or brown dwarfs. (There have also been several reported detections of planetary-mass objects that do not orbit any parent body.[৫৮] Some of these may have once belonged to a star's planetary system before being ejected from it; the term "rogue planet" is sometimes applied to such objects.)

However, the IAU's working definition is not universally accepted. One alternate suggestion is that planets should be distinguished from brown dwarfs on the basis of formation. It is widely believed that giant planets form through core accretion, and that process may sometimes produce planets with masses above the deuterium fusion threshold;[৫৯][৬০] massive planets of that sort may have already been observed.[৬১] This viewpoint also admits the possibility of sub-brown dwarfs, which have planetary masses but form like stars from the direct collapse of clouds of gas.

Also, the 13 Jupiter-mass cutoff does not have precise physical significance. Deuterium fusion can occur in some objects with mass below that cutoff. The amount of deuterium fused depends to some extent on the composition of the object.[৬২] The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia includes objects up to 25 Jupiter masses, saying, "The fact that there is no special feature around 13 MJup in the observed mass spectrum reinforces the choice to forget this mass limit,"[৬৩] and the Exoplanet Data Explorer includes objects up to 24 Jupiter masses with the advisory: "The 13 Jupiter-mass distinction by the IAU Working Group is physically unmotivated for planets with rocky cores, and observationally problematic due to the sin i ambiguity."[৬৪]

Nomenclature[সম্পাদনা]

Multiple-star standard[সম্পাদনা]

The convention for naming exoplanets is an extension of the one used by the Washington Multiplicity Catalog (WMC) for multiple-star systems, and adopted by the International Astronomical Union.[৬৫] The brightest member of a star system receives the letter "A". Distinct components not contained within "A" are labeled "B", "C", etc. Sub-components are designated by one or more suffixes with the primary label, starting with lowercase letters for the 2nd hierarchical level and then numbers for the 3rd.[৬৬] For example, if there is a triple star system in which two stars orbit each other closely while a third star is in a more distant orbit, the two closely orbiting stars would be named Aa and Ab, while the distant star would named B. For historical reasons, this standard is not always followed: for example Alpha Centauri A, B and C are not labelled Alpha Centauri Aa, Ab and B.

Extrasolar planet standard[সম্পাদনা]

Following an extension of the above standard, an exoplanet's name is normally formed by taking the name of its parent star and adding a lowercase letter. The first planet discovered in a system is given the designation "b" and later planets are given subsequent letters. If several planets in the same system are discovered at the same time, the closest one to the star gets the next letter, followed by the other planets in order of orbital size.

For instance, in the 55 Cancri system the first planet – 55 Cancri b – was discovered in 1996; two additional farther planets were simultaneously discovered in 2002 with the nearest to the star being named 55 Cancri c and the other 55 Cancri d; a fourth planet was claimed (its existence was later disputed) in 2004 and named 55 Cancri e despite lying closer to the star than 55 Cancri b; and the most recently discovered planet, in 2007, was named 55 Cancri f despite lying between 55 Cancri c and 55 Cancri d.[৬৭] As of April 2012 the highest letter in use is "j", for the unconfirmed planet HD 10180 j, and with "h" being the highest letter for a confirmed planet, belonging to the same host star).[৫]

If a planet orbits one member of a binary star system, then an uppercase letter for the star will be followed by a lowercase letter for the planet. Examples are 16 Cygni Bb[৬৮] and HD 178911 Bb.[৬৯] Planets orbiting the primary or "A" star should have 'Ab' after the name of the system, as in HD 41004 Ab.[৭০] However, the "A" is sometimes omitted; for example the first planet discovered around the primary star of the Tau Boötis binary system is usually called simply Tau Boötis b.[৭১]

If the parent star is a single star, then it may still be regarded as having an "A" designation, though the "A" is not normally written. The first exoplanet found to be orbiting such a star could then be regarded as a secondary sub-component that should be given the suffix "Ab". For example, 51 Peg Aa is the host star in the system 51 Peg; and the first exoplanet is then 51 Peg Ab. Since most exoplanets are in single star systems, the implicit "A" designation was simply dropped, leaving the exoplanet name with the lower-case letter only: 51 Peg b.

A few exoplanets have been given names that do not conform to the above standard. For example, the planets that orbit the pulsar PSR 1257 are often referred to with capital rather than lowercase letters. Also, the underlying name of the star system itself can follow several different systems. In fact, some stars (such as Kepler-11) have only received their names due to their inclusion in planet-search programs, previously only being referred to by their celestial coordinates.

Circumbinary planets and 2010 proposal[সম্পাদনা]

Hessman et al. state that the implicit system for exoplanet names utterly failed with the discovery of circumbinary planets.[৬৫] They note that the discoverers of the two planets around HW Virginis tried to circumvent the naming problem by calling them "HW Vir 3" and "HW Vir 4", i.e. the latter is the 4th object – stellar or planetary – discovered in the system. They also note that the discoverers of the two planets around NN Serpentis were confronted with multiple suggestions from various official sources and finally chose to use the designations "NN Ser c" and "NN Ser d".

The proposal of Hessman et al. starts with the following two rules:

- Rule 1. The formal name of an exoplanet is obtained by appending the appropriate suffixes to the formal name of the host star or stellar system. The upper hierarchy is defined by upper-case letters, followed by lower-case letters, followed by numbers, etc. The naming order within a hierarchical level is for the order of discovery only. (This rule corresponds to the present provisional WMC naming convention.)

- Rule 2. Whenever the leading capital letter designation is missing, this is interpreted as being an informal form with an implicit "A" unless otherwise explicitly stated. (This rule corresponds to the present exoplanet community usage for planets around single stars.)

They note that under these two proposed rules all of the present names for 99% of the planets around single stars are preserved as informal forms of the IAU sanctioned provisional standard. They would rename Tau Boötis b formally as Tau Boötis Ab, retaining the prior form as an informal usage (using Rule 2, above).

To deal with the difficulties relating to circumbinary planets, the proposal contains two further rules:

- Rule 3. As an alternative to the nomenclature standard in Rule 1, a hierarchical relationship can be expressed by concatenating the names of the higher order system and placing them in parentheses, after which the suffix for a lower order system is added.

- Rule 4. When in doubt (i.e. if a different name has not been clearly set in the literature), the hierarchy expressed by the nomenclature should correspond to dynamically distinct (sub-)systems in order of their dynamical relevance. The choice of hierarchical levels should be made to emphasize dynamical relationships, if known.

They submit that the new form using parentheses is the best for known circumbinary planets and has the desirable effect of giving these planets identical sub-level hierarchical labels and stellar component names which conform to the usage for binary stars. They say that it requires the complete renaming of only two exoplanetary systems: The planets around HW Virginis would be renamed HW Vir (AB) b & (AB) c, while those around NN Serpentis would be renamed NN Ser (AB) b & (AB) c. In addition the previously known single circumbinary planets around PSR B1620-26 and DP Leonis) can almost retain their names (PSR B1620-26 b and DP Leonis b) as unofficial informal forms of the "(AB)b" designation where the "(AB)" is left out.

The discoverers of the circumbinary planet around Kepler-16 followed the naming scheme proposed by Hessman et al. when naming the body Kepler-16 (AB)-b, or simply Kepler-16b when there is no ambiguity.[৭২]

Other naming systems[সম্পাদনা]

Another nomenclature, often seen in science fiction, uses Roman numerals in the order of planets' positions from the star. (This was inspired by an old system for naming moons of the outer planets, such as "Jupiter IV" for Callisto.) But such a system is impractical for scientific use, since new planets may be found closer to the star, changing all numerals.

Finally, several planets have received unofficial "real" names: notably Osiris (HD 209458 b), Bellerophon (51 Pegasi b), Zarmina (Gliese 581 g) and Methuselah (PSR B1620-26 b). W. Lyra of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy has suggested names mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known as of October 2009.[৭৩] In 2009 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) stated that it had no plans to assign names of this sort to extrasolar planets, considering it impractical.[৭৪] However, in August 2013 the IAU changed its stance, inviting members of the public to suggest names for extrasolar planets.[৭৫]

Planet-hosting stars[সম্পাদনা]

Proportion of stars with planets[সম্পাদনা]

Planet-search programs have discovered planets orbiting a substantial fraction of the stars they have looked at. However, the overall proportion of stars with planets is uncertain because not all planets can yet be detected. The radial-velocity method and the transit method (which between them are responsible for the vast majority of detections) are most sensitive to large planets in small orbits. Thus many known exoplanets are "hot Jupiters": planets of Jovian mass or larger in very small orbits with periods of only a few days. It is now estimated that 1% to 1.5% of sunlike stars possess such a planet, where "sunlike star" refers to any main-sequence star of spectral classes late-F, G, or early-K without a close stellar companion.[৭৬] It is further estimated that 3% to 4.5% of sunlike stars possess a giant planet with an orbital period of 100 days or less, where "giant planet" means a planet of at least 30 Earth masses.[৭৭]

The proportion of stars with smaller or more distant planets is less certain. It is known that small planets (of roughly Earth-like mass or somewhat larger) are more common than giant planets. It also appears that there are more planets in large orbits than in small orbits. Based on this, it is estimated that perhaps 20% of sunlike stars have at least one giant planet while at least 40% may have planets of lower mass.[৭৭][৭৮][৭৯] A 2012 study of gravitational microlensing data collected between 2002 and 2007 concludes the proportion of stars with planets is much higher and estimates an average of 1.6 planets orbiting between 0.5–10 AU per star in the Milky Way galaxy, the authors of this study conclude that "stars are orbited by planets as a rule, rather than the exception".[৩]

Whatever the proportion of stars with planets, the total number of exoplanets must be very large. Since our own Milky Way galaxy has at least 200 billion stars, it must also contain tens or hundreds of billions of planets.

In January 2013, astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) used Kepler's data to estimate that "at least 17 billion" Earth-sized exoplanets reside in the Milky Way Galaxy.[১০]

Multiple stars and star clusters[সম্পাদনা]

Most known planets orbit single stars, but some orbit one member of a binary star system,[৮০] and several circumbinary planets have been discovered which orbit around both members of binary star. A few planets in triple star systems are known[৮১] and one in the quadruple system Kepler 64. The open cluster NGC 6811 contains two known planetary systems Kepler 66 and Kepler 67. The globular cluster Messier 4 contains the planetary system PSR B1620-26.

Spectral classification[সম্পাদনা]

Most known exoplanets orbit stars roughly similar to the Sun, that is, main-sequence stars of spectral categories F, G, or K. One reason is that planet search programs have tended to concentrate on such stars. But in addition, statistical analysis indicates that lower-mass stars (red dwarfs, of spectral category M) are less likely to have planets massive enough to detect.[৭৭][৮২] Stars of spectral category A typically rotate very quickly, which makes it very difficult to measure the small Doppler shifts induced by orbiting planets since the spectral lines are very broad. However, this type of massive star eventually evolves into a cooler red giant which rotates more slowly and thus can be measured using the radial velocity method. As of early 2011 about 30 Jupiter class planets had been found around K-giant stars including Pollux, Gamma Cephei and Iota Draconis. Doppler surveys around a wide variety of stars indicate about 1 in 6 stars having twice the mass of the Sun are orbited by one or more Jupiter-sized planets, vs. 1 in 16 for Sun-like stars and only 1 in 50 for class M red dwarfs. On the other hand, microlensing surveys indicate that long-period Neptune-mass planets are found around 1 in 3 M dwarfs. [৮৩] Observations using the Spitzer Space Telescope indicate that extremely massive stars of spectral category O, which are much hotter than our Sun, produce a photo-evaporation effect that inhibits planetary formation.[৮৪]

Metallicity[সম্পাদনা]

Ordinary stars are composed mainly of the light elements hydrogen and helium. They also contain a small proportion of heavier elements, and this fraction is referred to as a star's metallicity (even if the elements are not metals in the traditional sense, such as iron). Giant planets are more likely to be found the higher the star's metallicity;[৭৬] however, smaller planets are present around stars with a wide range of metallicities.[৮৫] It has also been shown that stars with planets are more likely to be deficient in lithium.[৮৬]

Orbital parameters[সম্পাদনা]

Many planetary systems are not as placid as the Solar System, and have extreme orbital parameters and strongly interacting orbits, so that Kepler's laws do not hold in such systems.[৮৭]

Most known extrasolar planet candidates have been discovered using indirect methods and therefore only some of their physical and orbital parameters can be determined. For example, out of the six independent parameters that define an orbit, the radial-velocity method can determine four: semi-major axis, eccentricity, longitude of periastron, and time of periastron. Two parameters remain unknown: inclination and longitude of the ascending node.

Distance from star, semi-major axis and orbital period[সম্পাদনা]

For circular orbits, the semi-major axis is equal to the distance between the planet and the star. For elliptical orbits, the planet-star distance varies over the course of the orbit, in which case the semi-major axis is the average of the largest and smallest distances between the star and the planet. Orbital period is the time taken to complete one orbit. The shorter the semi-major axis, the shorter the orbital period.

There are exoplanets that are much closer to their parent star than any planet in the Solar System is to the Sun, and there are also exoplanets that are much further from their star. Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun at 0.4AU, takes 88-days for an orbit, but the shortest known orbits for exoplanets take only a few hours, e.g. Kepler-70b. The Kepler-11 system has five of its planets in shorter orbits than Mercury. Neptune is 30AU from the Sun and takes 165 years to orbit, but there are exoplanets that are hundreds of AU from their star and take more than a thousand years to orbit, e.g. 1RXS1609 b.

Over the lifetime of a star, the semi-major axes of its planets changes. This planetary migration happens especially during the formation of the planetary system when planets interact with the protoplanetary disk and each other until a relatively stable position is reached, and later in the red giant phase when the star expands and engulfs the nearest planets which can cause them to move inwards, and then as the star loses mass and shrinks to become a white dwarf causing planets to move outwards as a result of the star's reduced gravitational field.

The radial-velocity and transit methods are most sensitive to planets with small orbits. The earliest discoveries such as 51 Peg b were gas giants with orbits of a few days.[৭৭] These "hot Jupiters" likely formed further out and migrated inwards. The Kepler spacecraft has found planets with even shorter orbits of only a few hours, which places them within the star's upper atmosphere or corona, and these planets are Earth-sized or smaller and are probably the left-over solid cores of giant planets that have evaporated due to being so close to the star,[৮৮] or even being engulfed by the star in its red giant phase in the case of Kepler-70b. As well as evaporation, other reasons why larger planets are unlikely to survive orbits only a few hours long include orbital decay caused by tidal force, tidal-inflation instability, and Roche-lobe overflow[৮৯] The Roche limit implies that small planets with orbits of a few hours are likely made mostly of iron.[৮৯]

The direct imaging and microlensing methods are most sensitive to planets with large orbits, and have discovered some planets which have planet-star separations of hundreds of AU. However, protoplanetary disks are usually only around 100 AU in radius, and core accretion models predict giant planet formation to be within 10 AU, where the planets can coalesce quickly enough before the disk evaporates. This suggests that very long-period giant planets were formed close-in and gravitationally scattered outwards, or that the planet and star are a mass-imbalanced wide binary system with the planet being the primary object of its own separate protoplanetary disk. Gravitational instability models might produce planets at multi-hundred AU separations but this would require unusually large disks.[৯০]

Most planets that have been discovered are within a few AU of their star because the most used methods (radial-velocity and transit) require observation of several orbits to confirm that the planet exists and there has only been enough time elapsed since these methods were first used to cover separations of a few AU. A few planets with larger orbits have been discovered by direct imaging and microlensing but there is a middle range of distances, roughly equivalent to the Solar System's gas giant region, which is largely unexplored because it is mostly too close to the star for direct imaging or microlensing and too far out for the other methods. The first direct imaging equipment capable of exploring that region is being installed on the world's largest telescopes and should begin operation in 2014. e.g. Gemini Planet Imager and VLT-SPHERE. It appears plausible that in most exoplanetary systems, there are one or two giant planets with orbits comparable in size to those of Jupiter and Saturn in the Solar System. Giant planets with substantially larger orbits are now known to be rare, at least around Sun-like stars.[৯১]

The distance of the habitable zone from a star depends on the type of star and this distance changes during the star's lifetime as the size and temperature of the star changes.

Eccentricity[সম্পাদনা]

The eccentricity of an orbit is a measure of how elliptical (elongated) it is. Most exoplanets with orbital periods of 20 days or less have near-circular orbits, i.e. very low eccentricity. That is believed to be due to tidal circularization: reduction of eccentricity over time due to gravitational interaction between two bodies. By contrast, most known exoplanets with longer orbital periods have quite eccentric orbits. (As of July 2010, 55% of such exoplanets have eccentricities greater than 0.2 while 17% have eccentricities greater than 0.5.[৫]) Moderate to high eccentricities (e>0.2) of gas giant planets are is not an observational selection effect, since a planet can be detected about equally well regardless of the eccentricity of its orbit. The prevalence of elliptical orbits for giant planets is a major puzzle, since current theories of planetary formation strongly suggest planets should form with circular (that is, non-eccentric) orbits.[২৬] The prevalence of eccentric orbits may also indicate that the Solar System is unusual, since all of its planets except for Mercury have near-circular orbits.[৭৬]

However, when the Doppler signal of an extra-solar planet gets closer to the precision of the observations, the eccentricity becomes poorly constrained and biased towards higher values. It is suggested that some of the high eccentricity values reported for low-mass exoplanets may be overestimates, since simulations show that many observations are also consistent with two planets on circular orbits. Reported observations of single planets in moderately eccentric orbits have about a 15% chance of being a pair of planets.[৯২] This misinterpretation is especially likely if the two planets orbit with a 2:1 resonance. With the exoplanet sample known in 2009, a group of astronomers has concluded that "(1) around 35% of the published eccentric one-planet solutions are statistically indistinguishable from planetary systems in 2:1 orbital resonance, (2) another 40% cannot be statistically distinguished from a circular orbital solution" and "(3) planets with masses comparable to Earth could be hidden in known orbital solutions of eccentric super-Earths and Neptune mass planets".[৯৩]

Inclination[সম্পাদনা]

A combination of astrometric and radial velocity measurements has shown that some planetary systems contain planets whose orbital planes are significantly tilted relative to each other, unlike the Solar System.[৯৪] Research has now also shown that more than half of hot Jupiters have orbital planes substantially misaligned with their parent star's rotation. A substantial fraction even have retrograde orbits, meaning that they orbit in the opposite direction from the star's rotation.[৯৫] Andrew Cameron of the University of St Andrews stated "The new results really challenge the conventional wisdom that planets should always orbit in the same direction as their star's spin."[৯৬] Rather than a planet's orbit having been disturbed, it may be that the star itself flipped early in their system's formation due to interactions between the star's magnetic field and the planet-forming disc.[৯৭]

Resonances[সম্পাদনা]

Extrasolar planets with notable orbital parameters include KOI-730, which contains four planets in a 8:6:4:3 orbital resonance.[৯৮] This was originally thought to be 6:4:4:3, where one of the center planets was trapped in the other's L4 or L5 Lagrange point.[৯৯]

General properties of planets[সম্পাদনা]

Mass distribution[সম্পাদনা]

When a planet is found by the radial-velocity method, its orbital inclination i is unknown and can range from 0 to 90 degrees. The method is unable to determine the true mass (M) of the planet, but rather gives a lower limit for its mass M sini. In a few cases an apparent exoplanet may be a more massive object such as a brown dwarf or red dwarf. However, the probability of a small value of i (say less than 30 degrees, which would give a true mass at least double the observed lower limit) is relatively low (1-(√3)/2 ≈ 13%) and hence most planets will have true masses fairly close to the observed lower limit.[৭৭] Furthermore, if the planet's orbit is nearly perpendicular to the line of vision (i.e. i close to 90°), the planet can also be detected through the transit method. The inclination will then be known, and the planet's true mass can be found. Also, astrometric observations and dynamical considerations in multiple-planet systems can sometimes provide an upper limit to the planet's true mass.

As of September 2011, all but 50 of the many known exoplanets have more than ten times the mass of Earth.[৫] Many are considerably more massive than Jupiter, the most massive planet in the Solar System. However, these high masses are in large part due to an observational selection effect: all detection methods are more likely to discover massive planets. This bias makes statistical analysis difficult, but it appears that lower-mass planets are actually more common than higher-mass ones, at least within a broad mass range that includes all giant planets. In addition, the discovery of several planets only a few times more massive than Earth, despite the great difficulty of detecting them, indicates that such planets are fairly common.[৭৬]

The results from the first 43 days of the Kepler mission "imply that small candidate planets with periods less than 30 days are much more common than large candidate planets with periods less than 30 days and that the ground-based discoveries are sampling the large-size tail of the size distribution".[১৩]

Density and bulk composition[সম্পাদনা]

If a planet is detectable by both the radial-velocity and the transit methods, then both its true mass and its radius can be found. The planet's density can then be calculated. Planets with low density are inferred to be composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, while planets of intermediate density are inferred to have water as a major constituent. A planet of high density is believed to be rocky, like Earth and the other terrestrial planets of the Solar System. Researchers have developed user-friendly online tools to characterize the bulk composition of those planets.[১০০][১০১]

Many transiting exoplanets are much larger than expected given their mass, meaning that they have surprisingly low density. Several theories have been proposed to explain this observation, but none have yet been widely accepted among astronomers.[১০২]

Atmosphere[সম্পাদনা]

Spectroscopic measurements can be used to study a transiting planet's atmospheric composition.[১০৩] Water vapor, sodium vapor, methane, and carbon dioxide have been detected in the atmospheres of various exoplanets in this way.[১০৪][১০৫] The presence of oxygen may be detectable by ground-based telescopes.[১০৬] These techniques might conceivably discover atmospheric characteristics that suggest the presence of life on an exoplanet, but no such discovery has yet been made.

Another line of information about exoplanetary atmospheres comes from observations of orbital phase functions. Extrasolar planets have phases similar to the phases of the Moon. By observing the exact variation of brightness with phase, astronomers can calculate particle sizes in the atmospheres of planets.

Stellar light is polarized by atmospheric molecules; this could be detected with a polarimeter. So far[কখন?], one planet has been studied by polarimetry.

As of 2010, over two dozen exoplanet atmospheres have been observed, mostly of Hot Jupiters,[১০৭] resulting in detection of molecular spectral features; observation of day-night temperature gradients; and constraints on vertical atmospheric structure.

Temperature[সম্পাদনা]

One can estimate the temperature of an exoplanet based on the intensity of the light it receives from its parent star. For example, the planet OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb is estimated to have a surface temperature of roughly −220 °C (50 K). However, such estimates may be substantially in error because they depend on the planet's usually unknown albedo, and because factors such as the greenhouse effect may introduce unknown complications. A few planets have had their temperature measured by observing the variation in infrared radiation as the planet moves around in its orbit and is eclipsed by its parent star. For example, the planet HD 189733b has been found to have an average temperature of 1205±9 K (932±9 °C) on its dayside and 973±33 K (700±33 °C) on its nightside.[১০৮]

Other properties[সম্পাদনা]

On Earth-sized planets, plate tectonics is more likely if there are oceans of water; however, in 2007 two independent teams of researchers came to opposing conclusions about the likelihood of plate tectonics on larger super-earths[১০৯][১১০] with one team saying that plate tectonics would be episodic or stagnant[১১১] and the other team saying that plate tectonics is very likely on super-earths even if the planet is dry.[১১২]

The star 1SWASP J140747.93-394542.6 is orbited by an object that is possibly circled by rings although they are much larger than Saturn's rings so more like a cicrumplanetary disk in the process of forming moons. However the mass of the object is not known so it could be a brown dwarf or low-mass star instead of a planet.[১১৩]

KIC 12557548 b is a small rocky planet, very close to it star, that is evaporating and leaving a trailing tail of cloud and dust like a comet.[১১৪] The dust could be ash erupting from volcanoes and escaping due to the small planet's low surface-gravity, or it could be from metals that are vaporized by the high temperatures of being so close to the star with the metal vapor then condening into dust.[১১৫]

Other questions are how likely exoplanets are to possess moons and magnetospheres. No such moons and magnetospheres have yet been detected, but they may be fairly common.

Habitability[সম্পাদনা]

Several planets have orbits in their parent star's habitable zone, where it should be possible for liquid water to exist and for Earth-like conditions to prevail. Most of those planets are giant planets more similar to Jupiter than to Earth; if any of them have large moons, the moons might be a more plausible abode of life. Discovery of Gliese 581 g, thought to be a rocky planet orbiting in the middle of its star's habitable zone, was claimed in September 2010 and, if confirmed,[১১৬] it could be the most "Earth-like" extrasolar planet discovered to date.[১১৭] However, the existence of Gliese 581 g has been questioned or even discarded by other teams of astronomers; it is listed as unconfirmed at The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia.[১১৬]

Confirmed discoveries following the inconclusive detection of Gliese 581 g include the Kepler-22b, the first super-Earth located in the habitable zone of a Sun-like star.[১১৮] In September 2012, the discovery of two planets orbiting the red dwarf Gliese 163[১১৯] was announced.[১২০][১২১] One of the planets, Gliese 163 c, about 6.9 times the mass of Earth and somewhat hotter, was considered to be within the habitable zone.[১২০][১২১] In 2013, three more potentially habitable planets, Kepler-62 e, Kepler-62 f, and Kepler-69 c, orbiting Kepler-62 and Kepler-69 respectively, were discovered.[১২২][১২৩] All three planets were super-Earths[১২২] and may be covered by oceans thousands of kilometers deep.[১২৪] In June 2013, a dynamically packed planetary system around the nearby M dwarf Gliese 667C was announced. Such system would contain at least three super-Earths in its habitable zone (Gliese 667 Cc, Gliese 667 Ce and Gliese 667 Cf), establishing the new record in the number of potentially habitable worlds around a single star.[১২৫] The system contains two other planet candidates (Gliese 667 Cd and Gliese 667 Ch) which would lie in the cold/hot edges of the star's habitable zone. This later result highlights the prelevance of low mass stars as hosts of potentially habitable worlds.

Various estimates have been made as to how many planets might support simple or even intelligent life. However, these estimates have large uncertainties, because the complexity of cellular life may make biogenesis highly improbable. For example, Dr. Alan Boss of the Carnegie Institution of Science estimates there may be a "hundred billion" terrestrial planets in our Milky Way galaxy, many with simple life forms. He further believes there could be thousands of civilizations in our galaxy. Recent work by Duncan Forgan of Edinburgh University has also tried to estimate the number of intelligent civilizations in our galaxy. The research suggested there could be thousands of them, although presently there is no scientific evidence for extraterrestrial life. These estimates do not account for the unknown probability of the origins of life, but if life originates, it may spread among habitable planets by natural or directed panspermia.[১২৬]

Data from the Habitable Exoplanets Catalog (HEC) suggests that, of the 859 exoplanets which have been confirmed as of 3 January 2013, nine potentially habitable planets have been found, and the same source predicts that there may be 30 habitable extrasolar moons around confirmed planets.[১২৭] The HEC also states, of the 15,874 transit threshold crossing events (TCE) which have recurred more than three times (thus making them more likely to be actual planets) discovered by the Kepler probe up until 3 January 2013, that 262 planets (1.65%) have the potential to be habitable, with an additional 35 "warm jovian" planets which may have habitable natural satellites.[৭]

In February 2013, researchers calculated that up to 6% of small red dwarf stars may have planets with Earth-like properties. This suggests that there could be up to 4.5 billion such planets within our galaxy, and, statistically speaking, the closest "alien Earth" to the Solar System could be 13 light-years away.[১২৮]

Cultural impact[সম্পাদনা]

On May 9, 2013, a congressional hearing by two U. S. House of Representatives subcommittees discussed "Exoplanet Discoveries: Have We Found Other Earths?," prompted by the discovery of exoplanet Kepler-62f, along with Kepler-62e and Kepler-62c. A related special issue of the journal Science, published earlier, described the discovery of the exoplanets.[১২৯]

See also[সম্পাদনা]

Lists[সম্পাদনা]

- List of exoplanetary host stars

- List of extrasolar planets detected by microlensing

- List of extrasolar planets detected by radial velocity

- List of extrasolar planets detected by timing

- List of extrasolar planet extremes

- List of extrasolar planets that were directly imaged

- List of nearest terrestrial exoplanet candidates

- List of planetary systems

- List of transiting extrasolar planets

- List of unconfirmed exoplanets

Classifications[সম্পাদনা]

- Carbon planet

- Circumbinary planet

- Chthonian planet

- Coreless planet

- Eccentric Jupiter

- Extragalactic planet

- Extrasolar moon

- Gas giant

- Goldilocks planet

- Helium planet

- Hot Jupiter

- Hot Neptune

- Interstellar planet

- Iron planet

- Ocean planet

- Planetary system

- Pulsar planet

- Sudarsky extrasolar planet classification

- Super-Earth

- Terrestrial planet

Habitability and life[সম্পাদনা]

- Astrobiology

- Drake equation

- Extraterrestrial life

- Extraterrestrial liquid water

- Fermi paradox

- Hypothetical types of biochemistry

- Planetary habitability

- Rare Earth hypothesis

Observing programs and instruments[সম্পাদনা]

- Anglo-Australian Planet Search (AAPS)

- Automated Planet Finder at Lick Observatory

- California & Carnegie Planet Search

- CORALIE spectrograph

- East-Asian Planet Search Network (EAPSNet)

- EPICS for the European Extremely Large Telescope

- ESPRESSO is a new-generation spectrograph for ESO's VLT, capable of detecting Earth-like planets.

- FINDS Exo-Earths

- Gemini Planet Imager

- Geneva Extrasolar Planet Search

- HATNet Project (HAT)

- High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS)

- High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES)

- Magellan Planet Search Program

- MEarth Project

- Microlensing Follow-Up Network (MicroFUN)

- Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA)

- Okayama Planet Search Program

- Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE)

- PlanetPol

- PRL Advanced Radial-velocity All-sky Search (PARAS)

- Sagittarius Window Eclipsing Extrasolar Planet Search

- Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI)

- SOPHIE échelle spectrograph

- Subaru telescope, using the High-Contrast Coronographic Imager for Adaptive Optics (HiCIAO)

- SuperWASP (WASP)

- Systemic, an amateur search project

- Trans-Atlantic Exoplanet Survey (TrES)

- XO Telescope (XO)

- ZIMPOL/CHEOPS, based at VLT.

Missions[সম্পাদনা]

Current[সম্পাদনা]

Under development[সম্পাদনা]

- CHEOPS – launch in 2017

- Gaia – launch in November 2013.[৫২][৫৩][৫৪]

- James Webb Space Telescope

- TESS – launch in 2017

Proposed[সম্পাদনা]

- ATLAST

- EChO – for launch in 2024

- FINESSE

- New Worlds Mission – for launch in 2019

- PLATO – for launch in 2024

Canceled[সম্পাদনা]

Websites[সম্পাদনা]

References[সম্পাদনা]

- ↑ ক খ Claven, Whitney (৩ জানুয়ারি ২০১৩)। "Billions and Billions of Planets"। NASA। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ৩ জানুয়ারি ২০১৩।

- ↑ ক খ Staff (২ জানুয়ারি ২০১৩)। "100 Billion Alien Planets Fill Our Milky Way Galaxy: Study"। Space.com। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ৩ জানুয়ারি ২০১৩।

- ↑ ক খ গ Cassan, A; Kubas, D.; Beaulieu, J.-P.; Dominik, M.; Horne, K.; Greenhill, J.; Wambsganss, J.; Menzies, J.; Williams, A. (১১ জানুয়ারি ২০১২)। "One or more bound planets per Milky Way star from microlensing observations"। Nature। 481 (7380): 167–169। arXiv:1202.0903

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature10684। পিএমআইডি 22237108। বিবকোড:2012Natur.481..167C। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১২-০১-১১।

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature10684। পিএমআইডি 22237108। বিবকোড:2012Natur.481..167C। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১২-০১-১১।

- ↑ "Planet Population is Plentiful"। ESO Press Release। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ১৩ জানুয়ারি ২০১২।

- ↑ ক খ গ ঘ ঙ চ ছ Schneider, Jean (১০ সেপ্টেম্বর ২০১১)। "Interactive Extra-solar Planets Catalog"। The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১২-০৭-১৩।

- ↑ Detection of Potential Transit Signals in the First Twelve Quarters of Kepler Mission Data, 12 Dec 2012, Peter Tenenbaum, Jon M. Jenkins, Shawn Seader, Christopher J. Burke, Jessie L. Christiansen, Jason F. Rowe, Douglas A. Caldwell, Bruce D. Clarke, Jie Li, Elisa V. Quintana, Jeffrey C. Smith, Susan E. Thompson, Joseph D. Twicken, William J. Borucki, Natalie M. Batalha, Miles T. Cote, Michael R. Haas, Dwight T. Sanderfer, Forrest R. Girouard, Jennifer R. Hall, Khadeejah Ibrahim, Todd C. Klaus, Sean D. McCauliff, Christopher K. Middour, Anima Sabale, Akm Kamal Uddin, Bill Wohler, Thomas Barclay, Martin Still.

- ↑ ক খ "My God, it's full of planets! They should have sent a poet." (সংবাদ বিজ্ঞপ্তি)। Planetary Habitability Laboratory, University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo। ৩ জানুয়ারি ২০১২। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ৪ জানুয়ারি ২০১৩।

- ↑ Wall, Mike (১১ জানুয়ারি ২০১২)। "160 Billion Alien Planets May Exist in Our Milky Way Galaxy"। Space.com। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১২-০১-১১।

- ↑ Nomads of the Galaxy, Louis E. Strigari, Matteo Barnabe, Philip J. Marshall, Roger D. Blandford; estimates 700 objects >10−6 Solar masses (≈a Mars mass) per main sequence star between 0.08 and 1 Solar mass, of which there are billions in the Milky Way.

- ↑ ক খ গ Staff (৭ জানুয়ারি ২০১৩)। "17 Billion Earth-Size Alien Planets Inhabit Milky Way"। Space.com। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ৮ জানুয়ারি ২০১৩। উদ্ধৃতি ত্রুটি:

<ref>ট্যাগ বৈধ নয়; আলাদা বিষয়বস্তুর সঙ্গে "Space-20130107" নামটি একাধিক বার সংজ্ঞায়িত করা হয়েছে - ↑ ক খ দৃষ্টি আকর্ষণ: এই টেমপ্লেটি ({{cite doi}}) অবচিত। doi দ্বারা চিহ্নিত প্রকাশনা উদ্ধৃত করার জন্য:10.1038/355145a0, এর পরিবর্তে দয়া করে

|doi=10.1038/355145a0সহ {{সাময়িকী উদ্ধৃতি}} ব্যবহার করুন। - ↑ http://arxiv.org/ftp/astro-ph/papers/0603/0603200.pdf

- ↑ ক খ William J. Borucki, for the Kepler Team (২৩ জুলাই ২০১০)। "Characteristics of Kepler Planetary Candidates Based on the First Data Set: The Majority are Found to be Neptune-Size and Smaller"। arXiv:1012.0707v2

[astro-ph.SR]।

[astro-ph.SR]।

- ↑ Johnson, Michele (২০ ডিসেম্বর ২০১১)। "NASA Discovers First Earth-size Planets Beyond Our Solar System"। NASA। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১১-১২-২০।

- ↑ Hand, Eric (২০ ডিসেম্বর ২০১১)। "Kepler discovers first Earth-sized exoplanets"। Nature। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature.2011.9688।

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (২০ ডিসেম্বর ২০১১)। "Two Earth-Size Planets Are Discovered"। New York Times। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১১-১২-২১।

- ↑ "Terrestrial Planet Finder science goals: Detecting signs of life"। Terrestrial Planet Finder। JPL/NASA। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০০৬-০৭-২১।[অকার্যকর সংযোগ]

- ↑ Borucki, William J. (১৮ এপ্রিল ২০১৩)। "Kepler-62: A Five-Planet System with Planets of 1.4 and 1.6 Earth Radii in the Habitable Zone"। Science Express। arXiv:1304.7387

। ডিওআই:10.1126/science.1234702। বিবকোড:2013Sci...340..587B। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ১৮ এপ্রিল ২০১৩। অজানা প্যারামিটার

। ডিওআই:10.1126/science.1234702। বিবকোড:2013Sci...340..587B। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ১৮ এপ্রিল ২০১৩। অজানা প্যারামিটার |coauthors=উপেক্ষা করা হয়েছে (|author=ব্যবহারের পরামর্শ দেয়া হচ্ছে) (সাহায্য) - ↑ Giordano Bruno. On the Infinite Universe and Worlds (1584).

- ↑ Sheila Rabin, "Nicolaus Copernicus" in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (online. Retrieved 19 November 2005).

- ↑

Newton, Isaac (1999 [1713])। The Principia: A New Translation and Guide। University of California Press। পৃষ্ঠা 940। আইএসবিএন 0-520-20217-1। অজানা প্যারামিটার

|coauthors=উপেক্ষা করা হয়েছে (|author=ব্যবহারের পরামর্শ দেয়া হচ্ছে) (সাহায্য); এখানে তারিখের মান পরীক্ষা করুন:|তারিখ=(সাহায্য) - ↑ W. S. Jacob (১৮৫৫)। "On Certain Anomalies presented by the Binary Star 70 Ophiuchi"। Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society। 15: 228। বিবকোড:1855MNRAS..15..228J।

- ↑ T. J. J. See (১৮৯৬)। "Researches on the Orbit of F.70 Ophiuchi, and on a Periodic Perturbation in the Motion of the System Arising from the Action of an Unseen Body"। Astronomical Journal। 16: 17। ডিওআই:10.1086/102368। বিবকোড:1896AJ.....16...17S।

- ↑ T. J. Sherrill (১৯৯৯)। "A Career of Controversy: The Anomaly of T. J. J. See" (পিডিএফ)। Journal for the History of Astronomy। 30 (98): 25–50। বিবকোড:1999JHA....30...25S।

- ↑ P. van de Kamp (১৯৬৯)। "Alternate dynamical analysis of Barnard's star"। Astronomical Journal। 74: 757–759। ডিওআই:10.1086/110852। বিবকোড:1969AJ.....74..757V।

- ↑ ক খ Boss, Alan (২০০৯)। The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets। Basic Books। পৃষ্ঠা 31–32। আইএসবিএন 978-0-465-00936-7। উদ্ধৃতি ত্রুটি:

<ref>ট্যাগ বৈধ নয়; আলাদা বিষয়বস্তুর সঙ্গে "boss_book" নামটি একাধিক বার সংজ্ঞায়িত করা হয়েছে - ↑ M. Bailes, A. G. Lyne, S. L. Shemar (১৯৯১)। "A planet orbiting the neutron star PSR1829-10"। নেচার। 352 (6333): 311–313। ডিওআই:10.1038/352311a0। বিবকোড:1991Natur.352..311B।

- ↑ A. G. Lyne, M. Bailes (১৯৯২)। "No planet orbiting PS R1829-10"। নেচার। 355 (6357): 213। ডিওআই:10.1038/355213b0। বিবকোড:1992Natur.355..213L।

- ↑ দৃষ্টি আকর্ষণ: এই টেমপ্লেটি ({{cite doi}}) অবচিত। doi দ্বারা চিহ্নিত প্রকাশনা উদ্ধৃত করার জন্য:10.1086/166608, এর পরিবর্তে দয়া করে

|doi=10.1086/166608সহ {{সাময়িকী উদ্ধৃতি}} ব্যবহার করুন। - ↑ A. T. Lawton, P. Wright; Wright (১৯৮৯)। "A planetary system for Gamma Cephei?"। Journal of the British Interplanetary Society। 42: 335–336। বিবকোড:1989JBIS...42..335L।

- ↑ G. A. H. Walker; Bohlender, David A.; Walker, Andrew R.; Irwin, Alan W.; Yang, Stephenson L. S.; Larson, Ana (১৯৯২)। "Gamma Cephei – Rotation or planetary companion?"। Astrophysical Journal Letters। 396 (2): L91–L94। ডিওআই:10.1086/186524। বিবকোড:1992ApJ...396L..91W।

- ↑

A. P. Hatzes; Cochran, William D.; Endl, Michael; McArthur, Barbara; Paulson, Diane B.; Walker, Gordon A. H.; Campbell, Bruce; Yang, Stephenson (২০০৩)। "A Planetary Companion to Gamma Cephei A"। Astrophysical Journal। 599 (2): 1383–1394। arXiv:astro-ph/0305110

। ডিওআই:10.1086/379281। বিবকোড:2003ApJ...599.1383H।

। ডিওআই:10.1086/379281। বিবকোড:2003ApJ...599.1383H।

- ↑ Holtz, Robert (২২ এপ্রিল ১৯৯২)। "Scientists Uncover Evidence of New Planets Orbiting Star" (republished in The Tech)। Los Angeles Times।

- ↑ M. Mayor, D. Queloz (১৯৯৫)। "A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star"। Nature। 378 (6555): 355–359। ডিওআই:10.1038/378355a0। বিবকোড:1995Natur.378..355M।

- ↑ Jack J. Lissauer (১৯৯৯)। "Three Planets for Upsilon Andromedae"। Nature। 398 (659): 659। ডিওআই:10.1038/19409। বিবকোড:1999Natur.398..659L।

- ↑ Laurence R. Doyle; Carter, J. A.; Fabrycky, D. C.; Slawson, R. W.; Howell, S. B.; Winn, J. N.; Orosz, J. A.; Pr Sa, A.; Welsh, W. F. (১৬ সেপ্টেম্বর ২০১১)। "Kepler-16: A Transiting Circumbinary Planet"। Science। 333 (6049): 1602–6। arXiv:1109.3432

। ডিওআই:10.1126/science.1210923। পিএমআইডি 21921192। বিবকোড:2011Sci...333.1602D।

। ডিওআই:10.1126/science.1210923। পিএমআইডি 21921192। বিবকোড:2011Sci...333.1602D।

- ↑ Batalha, Natalie; Rowe; Bryson; Burke; Caldwell; Christiansen; Thompson (২৭ ফেব্রুয়ারি ২০১২)। "Planetary Candidates observed by Kepler III:Analysis of the first 16 Months of Data"। arXiv:1202.5852

[astro-ph.EP]। একের অধিক

[astro-ph.EP]। একের অধিক |author=এবং|last=উল্লেখ করা হয়েছে (সাহায্য); Authors list-এ|শেষাংশ4=অনুপস্থিত (সাহায্য); Authors list-এ|শেষাংশ8=অনুপস্থিত (সাহায্য) - ↑ Whoa! Earth-size planet in Alpha Centauri system

- ↑ Perryman, Michael (২০১১)। The Exoplanet Handbook। Cambridge University Press। পৃষ্ঠা 149। আইএসবিএন 978-0-521-76559-6।

- ↑

F. Pepe, C. Lovis, D. Segransan; ও অন্যান্য (২০১১)। "The HARPS search for Earth-like planets in the habitable zone"। Astronomy & Astrophysics। 534: A58। arXiv:1108.3447

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361/201117055। বিবকোড:2011A&A...534A..58P।

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361/201117055। বিবকোড:2011A&A...534A..58P।

- ↑ Weighing The Non-Transiting Hot Jupiter Tau BOO b, Florian Rodler, Mercedes Lopez-Morales, Ignasi Ribas, 27 June 2012.

- ↑ http://www.scientificcomputing.com/news-DS-Planet-Hunting-Finding-Earth-like-Planets-071910.aspx "Planet Hunting: Finding Earth-like Planets"

- ↑ Ballard; Francois Fressin; David Charbonneau; Jean-Michel Desert; Guillermo Torres; Geoffrey Marcy; Burke; Howard Isaacson; ও অন্যান্য (২০১১)। "The Kepler-19 System: A Transiting 2.2 R_Earth Planet and a Second Planet Detected via Transit Timing Variations"। arXiv:1109.1561

[astro-ph.EP]।

[astro-ph.EP]।

- ↑

Jack J. Lissauer, Daniel C. Fabrycky, Eric B. Ford; ও অন্যান্য (২০১১)। "A closely packed system of low-mass, low-density planets transiting Kepler-11"। Nature। 470 (7332): 53। arXiv:1102.0291

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature09760। বিবকোড:2011Natur.470...53L। ৩০ নভেম্বর ২০১১ তারিখে মূল থেকে আর্কাইভ করা।

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature09760। বিবকোড:2011Natur.470...53L। ৩০ নভেম্বর ২০১১ তারিখে মূল থেকে আর্কাইভ করা।

- ↑ Pal; Kocsis (২০০৮)। "Periastron Precession Measurements in Transiting Extrasolar Planetary Systems at the Level of General Relativity"। arXiv:0806.0629

[astro-ph]।

[astro-ph]।

- ↑ Nature। "A giant planet orbiting the /`extreme horizontal branch/' star V[thinsp]391 Pegasi : Abstract"। Nature। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১৩-০৯-১৯।

- ↑ Jenkins, J.M. (২০০৩-০৯-২০)। "Detecting reflected light from close-in giant planets using space-based photometers" (PDF)। Astrophysical Journal। 1 (595): 429–445। arXiv:astro-ph/0305473

। ডিওআই:10.1086/377165। বিবকোড:2003ApJ...595..429J। অজানা প্যারামিটার

। ডিওআই:10.1086/377165। বিবকোড:2003ApJ...595..429J। অজানা প্যারামিটার |coauthors=উপেক্ষা করা হয়েছে (|author=ব্যবহারের পরামর্শ দেয়া হচ্ছে) (সাহায্য) - ↑ http://iopscience.iop.org/1538-4357/588/2/L117/pdf/17192.web.pdf

- ↑ http://www.universetoday.com/102112/using-the-theory-of-relativity-and-beer-to-find-exoplanets/

- ↑ Schmid, H. M.; Beuzit, J.-L.; Feldt, M.; ও অন্যান্য (২০০৬)। "Search and investigation of extra-solar planets with polarimetry"। Direct Imaging of Exoplanets: Science & Techniques. Proceedings of the IAU Colloquium #200। 1 (C200): 165–170। ডিওআই:10.1017/S1743921306009252। বিবকোড:2006dies.conf..165S।

- ↑ Berdyugina, Svetlana V. (২০০৮)। "First detection of polarized scattered light from an exoplanetary atmosphere" (পিডিএফ)। The Astrophysical Journal। 673: L83। arXiv:0712.0193

। ডিওআই:10.1086/527320। বিবকোড:2008ApJ...673L..83B। অজানা প্যারামিটার

। ডিওআই:10.1086/527320। বিবকোড:2008ApJ...673L..83B। অজানা প্যারামিটার |month=উপেক্ষা করা হয়েছে (সাহায্য); অজানা প্যারামিটার|coauthors=উপেক্ষা করা হয়েছে (|author=ব্যবহারের পরামর্শ দেয়া হচ্ছে) (সাহায্য) - ↑ ক খ http://www.rssd.esa.int/index.php?project=GAIA&page=index

- ↑ ক খ Staff (১৯ নভেম্বর ২০১২)। "Announcement of Opportunity for the Gaia Data Processing Archive Access Co-Ordination Unit"। ESA। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ১৭ মার্চ ২০১৩।

- ↑ ক খ Staff (৩০ জানুয়ারি ২০১২)। "DPAC Newsletter no. 15" (PDF)। European Space Agency। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ১৬ মার্চ ২০১৩।

- ↑ "IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes"। ২০০৬। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১০-০৪-২৫।

- ↑ R. R. Brit (২০০৬)। "Why Planets Will Never Be Defined"। Space.com। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০০৮-০২-১৩।

- ↑ "Working Group on Extrasolar Planets: Definition of a "Planet""। IAU position statement। ২৮ ফেব্রুয়ারি ২০০৩। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০০৬-০৯-০৯।

- ↑

Kenneth A. Marsh, J. Davy Kirkpatrick, Peter Plavchan (২০১০)। "A Young Planetary-Mass Object in the rho Oph Cloud Core"। Astrophysical Journal Letters। 709 (2): L158। arXiv:0912.3774

। ডিওআই:10.1088/2041-8205/709/2/L158। বিবকোড:2010ApJ...709L.158M।

। ডিওআই:10.1088/2041-8205/709/2/L158। বিবকোড:2010ApJ...709L.158M।

- ↑ Mordasini, C.; ও অন্যান্য (২০০৭)। "Giant Planet Formation by Core Accretion"। arXiv:0710.5667

[astro-ph]। অজানা প্যারামিটার

[astro-ph]। অজানা প্যারামিটার |version=উপেক্ষা করা হয়েছে (সাহায্য) - ↑ Baraffe, I.; Chabrier, G.; Barman, T. (২০০৮)। "Structure and evolution of super-Earth to super-Jupiter exoplanets. I. Heavy element enrichment in the interior"। Astronomy and Astrophysics। 482 (1): 315–332। arXiv:0802.1810

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361:20079321। বিবকোড:2008A&A...482..315B।

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361:20079321। বিবকোড:2008A&A...482..315B।

- ↑ Bouchy, F.; Hébrard, G.; Udry, S.; Delfosse, X.; Boisse, I.; Desort, M.; Bonfils, X.; Eggenberger, A.; Ehrenreich, D. (২০০৯)। "The SOPHIE search for northern extrasolar planets. I. A companion around HD 16760 with mass close to the planet/brown-dwarf transition"। Astronomy and Astrophysics। 505 (2): 853–858। arXiv:0907.3559

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361/200912427। বিবকোড:2009A&A...505..853B।

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361/200912427। বিবকোড:2009A&A...505..853B।

- ↑ Spiegel; Adam Burrows; Milsom (২০১০)। "The Deuterium-Burning Mass Limit for Brown Dwarfs and Giant Planets"। arXiv:1008.5150

[astro-ph.EP]।

[astro-ph.EP]।

- ↑ Jean Schneider; Cyrill Dedieu; Pierre Le Sidaner; Renaud Savalle; Ivan Zolotukhin (২০১১)। "Defining and cataloging exoplanets: The exoplanet.eu database"। Astron. & Astrophys.। 532 (79): A79। arXiv:1106.0586

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361/201116713। বিবকোড:2011A&A...532A..79S।

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361/201116713। বিবকোড:2011A&A...532A..79S।

- ↑ Jason T. Wright; Onsi Fakhouri; Marcy; Eunkyu Han; Ying Feng; John Asher Johnson; Howard; Fischer; Valenti (২০১০)। "The Exoplanet Orbit Database"। arXiv:1012.5676

[astro-ph.SR]।

[astro-ph.SR]।

- ↑ ক খ Hessman, F. V.; Dhillon, V. S.; Winget, D. E.; Schreiber, M. R.; Horne, K.; Marsh, T. R.; Guenther, E.; Schwope, A.; Heber, U. (২০১০)। "On the naming convention used for multiple star systems and extrasolar planets"। arXiv:1012.0707

[astro-ph.SR]। অজানা প্যারামিটার

[astro-ph.SR]। অজানা প্যারামিটার |bibcode=উপেক্ষা করা হয়েছে (সাহায্য) - ↑ William I. Hartkopf & Brian D. Mason। "Addressing confusion in double star nomenclature: The Washington Multiplicity Catalog"। United States Naval Observatory। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০০৮-০৯-১২।

- ↑ Jean Schneider (২০১১)। "Notes for star 55 Cnc"। Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৬ সেপ্টেম্বর ২০১১।

- ↑ Jean Schneider (২০১১)। "Notes for Planet 16 Cyg B b"। Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৬ সেপ্টেম্বর ২০১১।

- ↑ Jean Schneider (২০১১)। "Notes for Planet HD 178911 B b"। Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৬ সেপ্টেম্বর ২০১১।

- ↑ Jean Schneider (২০১১)। "Notes for Planet HD 41004 A b"। Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৬ সেপ্টেম্বর ২০১১।

- ↑ Jean Schneider (২০১১)। "Notes for Planet Tau Boo b"। Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৬ সেপ্টেম্বর ২০১১।

- ↑ Doyle, Laurance R.; Carter, Joshua A.; Fabrycky, Daniel C.; Slawson, Robert W.; Howell, Steve B.; Winn, Joshua N.; Orosz, Jerome A.; Prša, Andrej; Welsh, William F. (২০১১)। "Kepler-16: A Transiting Circumbinary Planet"। Science। 333 (6049): 1602–6। arXiv:1109.3432

। ডিওআই:10.1126/science.1210923। পিএমআইডি 21921192। বিবকোড:2011Sci...333.1602D।

। ডিওআই:10.1126/science.1210923। পিএমআইডি 21921192। বিবকোড:2011Sci...333.1602D।

- ↑ Lyra, W. (২০০৯)। "Naming the extrasolar planets"। arXiv:0910.3989v3

[astro-ph.EP]।

[astro-ph.EP]।

- ↑ "Planets Around Other Stars"। International Astronomical Union। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০০৯-১২-০৬।

- ↑ "Public Naming of Planets and Planetary Satellites" (পিডিএফ)। International Astronomical Union। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১৩-০৮-১৯।

- ↑ ক খ গ ঘ

G. Marcy; Butler, R. Paul; Fischer, Debra; Vogt, Steven; Wright, Jason T.; Tinney, Chris G.; Jones, Hugh R. A. (২০০৫)। "Observed Properties of Exoplanets: Masses, Orbits and Metallicities"। Progress of Theoretical Physics Supplement। 158: 24–42। arXiv:astro-ph/0505003

। ডিওআই:10.1143/PTPS.158.24। বিবকোড:2005PThPS.158...24M।

। ডিওআই:10.1143/PTPS.158.24। বিবকোড:2005PThPS.158...24M।

- ↑ ক খ গ ঘ ঙ Andrew Cumming; R. Paul Butler; Geoffrey W. Marcy; ও অন্যান্য (২০০৮)। "The Keck Planet Search: Detectability and the Minimum Mass and Orbital Period Distribution of Extrasolar Planets"। Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific। 120 (867): 531–554। arXiv:0803.3357

। ডিওআই:10.1086/588487। বিবকোড:2008PASP..120..531C।

। ডিওআই:10.1086/588487। বিবকোড:2008PASP..120..531C।

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (১৯ অক্টোবর ২০০৯)। "Scientists announce planet bounty"। BBC News। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১০-০৩-৩১।

- ↑ David P. Bennett, Jay Anderson, Ian A. Bond, Andrzej Udalski, Andrew Gould (২০০৬)। "Identification of the OGLE-2003-BLG-235/MOA-2003-BLG-53 Planetary Host Star"। Astrophysical Journal Letters। 647 (2): L171–L174। arXiv:astro-ph/0606038

। ডিওআই:10.1086/507585। বিবকোড:2006ApJ...647L.171B।

। ডিওআই:10.1086/507585। বিবকোড:2006ApJ...647L.171B।

- ↑ BINARY CATALOGUE OF EXOPLANETS, Maintained by Richard Schwarz], retrieved 28 Sept 2013

- ↑ http://www.univie.ac.at/adg/schwarz/multi.html

- ↑

X. Bonfils; Forveille, T.; Delfosse, X.; Udry, S.; Mayor, M.; Perrier, C.; Bouchy, F.; Pepe, F.; Queloz, D. (২০০৫)। "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets: VI. A Neptune-mass planet around the nearby M dwarf Gl 581"। Astronomy & Astrophysics। 443 (3): L15–L18। arXiv:astro-ph/0509211

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361:200500193। বিবকোড:2005A&A...443L..15B।

। ডিওআই:10.1051/0004-6361:200500193। বিবকোড:2005A&A...443L..15B।

- ↑ J. A. Johnson (২০১১)। "The Stars that Host Planets"। Sky & Telescope (April): 22–27।

- ↑ L. Vu (৩ অক্টোবর ২০০৬)। "Planets Prefer Safe Neighborhoods"। Spitzer Science Center। ১৩ জুলাই ২০০৭ তারিখে মূল থেকে আর্কাইভ করা। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০০৭-০৯-০১।

- ↑ An abundance of small exoplanets around stars with a wide range of metallicities, Nature, Received 23 December 2011, Accepted 5 April 2012, Published online 13 June 2012.

- ↑

G. Israelian; Mena, Elisa Delgado; Santos, Nuno C.; Sousa, Sergio G.; Mayor, Michel; Udry, Stephane; Cerdeña, Carolina Domínguez; Rebolo, Rafael; Randich, Sofia (২০০৯)। "Enhanced lithium depletion in Sun-like stars with orbiting planets"। Nature। 462 (7270): 189–191। arXiv:0911.4198

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature08483। পিএমআইডি 19907489। বিবকোড:2009Natur.462..189I।

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature08483। পিএমআইডি 19907489। বিবকোড:2009Natur.462..189I।

- ↑ Non-Keplerian Dynamics, Daniel C. Fabrycky, 2010, Chapter in EXOPLANETS, ed. S. Seager, University of Arizona Press, 2011.

- ↑ Time Really Flies on These Kepler Planets

- ↑ ক খ The Roche limit for close-orbiting planets: Minimum density, composition constraints, and application to the 4.2-hour planet KOI 1843.03, Saul Rappaport, Roberto Sanchis-Ojeda, Leslie A. Rogers, Alan Levine, Joshua N. Winn, 15 Jul 2013

- ↑ LONG-PERIOD EXOPLANETS FROM DYNAMICAL RELAXATION, Caleb Scharf and Kristen Menou, The Astrophysical Journal, 693:L113–L117, 2009 March 10

- ↑

Eric L. Nielsen and Laird M. Close (২০১০)। "A Uniform Analysis of 118 Stars with High-Contrast Imaging: Long-Period Extrasolar Giant Planets are Rare around Sun-like Stars"। Astrophysical Journal। 717 (2): 878। arXiv:0909.4531

। ডিওআই:10.1088/0004-637X/717/2/878। বিবকোড:2010ApJ...717..878N।

। ডিওআই:10.1088/0004-637X/717/2/878। বিবকোড:2010ApJ...717..878N।

- ↑

T. Rodigas; Hinz (২০০৯)। "Which Radial Velocity Exoplanets Have Undetected Outer Companions?"। Astrophys.J.। 702: 716–723। arXiv:0907.0020

। ডিওআই:10.1088/0004-637X/702/1/716। বিবকোড:2009ApJ...702..716R।

। ডিওআই:10.1088/0004-637X/702/1/716। বিবকোড:2009ApJ...702..716R।

- ↑

Guillem Anglada-Escudé, Mercedes López-Morales and John E. Chambers (২০১০)। "How Eccentric Orbital Solutions Can Hide Planetary Systems in 2:1 Resonant Orbits"। Astrophysical Journal। 709 (1): 168। arXiv:0809.1275

। ডিওআই:10.1088/0004-637X/709/1/168। বিবকোড:2010ApJ...709..168A।

। ডিওআই:10.1088/0004-637X/709/1/168। বিবকোড:2010ApJ...709..168A।

- ↑ Out of Flatland: Orbits Are Askew in a Nearby Planetary System, www.scientificamerican.com, 24 May 2010.

- ↑ "Turning planetary theory upside down"। Astro.gla.ac.uk। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১২-০২-২৮।

- ↑ "Dropping a Bomb About Exoplanets"। Universe Today। ১৩ এপ্রিল ২০০৯। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২০১০-০৪-১৩।

- ↑ Tilting stars may explain backwards planets, New Scientist, 1 September 2010, Magazine issue 2776.

- ↑ Emspak, Jesse। "Kepler Finds Bizarre Systems"। International Business Times। International Business Times Inc.। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২ মার্চ ২০১১।

- ↑ Beatty, Kelly (২০১১)। "Kepler Finds Planets in Tight Dance"। Sky and Telescope। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ১১ মার্চ ২০১১।

- ↑ www.astrozeng.com

- ↑ Li Zeng, and Dimitar Sasselov. "A Detailed Model Grid for Solid Planets from 0.1 through 100 Earth Masses". In the Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific (PASP), Chicago Journals, Volume 125, No. 925, pp. 227-239, March 2013.

- ↑ I. Baraffe and G. Chabrier and T. Barman (২০১০)। "The physical properties of extra-solar planets"। Reports on Progress in Physics। 73 (16901): 1। arXiv:1001.3577

। ডিওআই:10.1088/0034-4885/73/1/016901। বিবকোড:2010RPPh...73a6901B।

। ডিওআই:10.1088/0034-4885/73/1/016901। বিবকোড:2010RPPh...73a6901B।

- ↑

D. Charbonneau, T. Brown; A. Burrows; G. Laughlin (২০০৬)। "When Extrasolar Planets Transit Their Parent Stars"। Protostars and Planets V। University of Arizona Press। arXiv:astro-ph/0603376

।

।

- ↑ Brogi, Matteo; Snellen, Ignas A. G.; de Krok, Remco J.; Albrecht, Simon; Birkby, Jayne; de Mooij, Ernest J. W. (২৮ জুন ২০১২)। "The signature of orbital motion from the dayside of the planet t Boötis b"। Nature। 486: 502–504। arXiv:1206.6109

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature11161। বিবকোড:2012Natur.486..502B। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৮ জুন ২০১২।

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature11161। বিবকোড:2012Natur.486..502B। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৮ জুন ২০১২।

- ↑ Mann, Adam (২৭ জুন ২০১২)। "New View of Exoplanets Will Aid Search for E.T."। Wired (magazine)। সংগ্রহের তারিখ ২৮ জুন ২০১২।

- ↑ "Can Ground-based Telescopes Detect The Oxygen 1.27 Micron Absorption Feature as a Biomarker in Exoplanets?" The Astrophysical Journal, 758, 13 (2012)

- ↑ Exoplanet Atmospheres, S. Seager, D. Deming, 2010

- ↑

Heather Knutson, David Charbonneau, Lori Allen; ও অন্যান্য (২০০৭)। "A map of the day-night contrast of the extrasolar planet HD 189733b"। Nature। 447 (7141): 183–186। arXiv:0705.0993

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature05782। পিএমআইডি 17495920। বিবকোড:2007Natur.447..183K।

। ডিওআই:10.1038/nature05782। পিএমআইডি 17495920। বিবকোড:2007Natur.447..183K।

- ↑ Convection scaling and subduction on Earth and super-Earths, Diana Valencia, Richard J. O'Connell, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 286, Issues 3–4, 15 September 2009, Pages 492–502, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.015,

- ↑ Plate tectonics on super-Earths: Equally or more likely than on Earth, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.07.029, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 310, Issues 3–4, 15 October 2011, Pages 252–261, H. J. van Heck, P. J. Tackley.